Crack epidemic means new front in war on drugs

By Mario Osava | Last updated: Dec 3, 2009 - 2:17:16 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

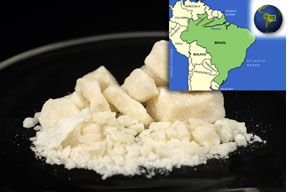

Photo: DEA.gov

|

Within a few weeks of running away, the boy, who is now 12, had joined the legion of crack addicts wandering the streets of Brazil's big cities. Joao is not his real name.

In Rio de Janeiro, between 80 and 90 percent of homeless people are addicted to crack—a cheaper, potent, highly addictive form of cocaine that is sold in small chunks and smoked rather than snorted—according to estimates by mental health professionals and social workers who try to help this segment of the population.

The amount of crack seized by the police this year in Rio was six times the total confiscated in 2008. A growing majority of children and adolescents receiving assistance from municipal services say they use crack.

In response, the Rio city government is opening special treatment centers for crack addicts.

The expansion of crack, which is especially visible at some city squares and streets where addicts congregate, has mainly occurred among the poor. But the drug has also made headway among better-off sectors of the population.

The magnitude of this urban epidemic was catapulted to the headlines when Bruno Kligierman de Melo, a 26-year-old guitar player, killed his friend Barbara Calazans, an 18-year-old student, on Oct. 24. According to the police, he strangled her in a fit of madness brought on by crack, which he had been using for six years.

Drug consumption, which was preceded by alcohol use in school, turned “a good person into a murderer,” lamented his father, Luiz Proa, in an open letter in which he called for drug addicts to be forced into treatment, contrary to the prevailing wisdom, according to which drug treatment must be voluntary in order to be effective.

The proliferation of crack represents a new challenge for Brazil in terms of counter-drug action, at a time when President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva himself acknowledges that the country's anti-drug policies have been ineffective.

The Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy, created in 2008 and headed by former presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2003) of Brazil, César Gaviria (1990-1994) of Colombia, and Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000) of Mexico, said in its report, released in February, that the “war on drugs” was a failure.

The recommendations put forth by the commission, made up of 17 personalities from Latin America, included the decriminalization of marijuana for personal use, the treatment of drug addiction as a public health problem, and a refocusing of public policies to make the fight against organized crime a top priority.

As a cheap, fast-acting drug that provides an intense high, crack is popular among consumers, which also makes it attractive to drug dealers and traffickers because it is “good business,” psychiatrist Carlos Salgado, president of the Brazilian Association of Studies on Alcohol and Other Drugs, told IPS.

The fact that the high is so immediate, intense and short-lived drives addicts to constantly be looking for their next fix, and many smoke crack dozens of times a day, he explained.

J. started smoking crack with “a 40-year-old guy.”

“I felt really good, and strong”—a pleasant sensation he had never experienced before, he told IPS. It was different from what he had felt when he drank alcohol or smoked a cigarette—his first drugs; smoked marijuana—which he doesn't like because it makes him hungry and sleepy; or snorted cocaine, “which didn't do anything for me.”

The man who turned him on to drugs also introduced him to petty drug dealing. Adding up what he takes in by dealing drugs and panhandling, J. says he makes between $29 to $41 a day—all of which he spends on crack.

A pebble of crack costs five reals, about $2.90, but it is only enough for two highs—a few minutes of pleasure. Larger rocks cost twice that.

J. says it's easier to get the small amount of food that he needs—because the drug takes away his appetite—by begging. The same goes for clothes.

Around a dozen people “from ages four to 60” are his “colleagues” on the streets of a neighborhood near the center of Rio. The police don't bother them.

J. admits that he is illiterate, and says he has no dreams for the future. “All I need are these little rocks,” he says. Nor does he worry about the health threats posed by crack, which according to Salgado causes terrible damages to the brain, heart, liver, kidneys and lungs, cutting short the lives of addicts.

The massive use of crack is a recent phenomenon in Rio, having spread here years after it took root in Sao Paulo to the south, where parts of the city have become “cracolandias” or “cracklands.”

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!