The Congo of America: The Slave Trade of Washington, D.C.

By Tingba Muhammad -Guest Columnist- | Last updated: Aug 16, 2012 - 8:00:50 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

A close reading of the newspaper advertisements placed by American slave traders shows that Blacks were skilled craftsmen at the highest level. It is easy to find ads by White people selling “engineers,” “carpenters,” “mechanics,” “brick masons,” “nurses,” “blacksmiths,” and “bakers.” Blacks so dominated these trades that after the so-called emancipation in 1863, it was said that if a White man were seen doing ANY of this kind of work, it would draw a crowd of gawking onlookers. Blacks built America—just as they built the pyramids in Egypt and then gave civilization to Europe.

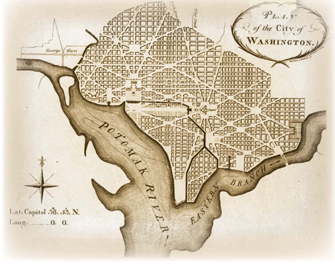

The U.S. Constitution forbade the trans-Atlantic slave trade after 1808. This gave rise to the false assumption that there was significant anti-slavery sentiment among America’s leaders. The fact is that the internal trade in Blacks bred by White Americans, such as those 350 slaves on George Washington’s plantation, provided such a large profit that White America would not permit any foreign competition in slaves from Africa. This prohibition only accelerated the domestic slave-breeding trade, which only increased and intensified the unceasing hell Black women suffered as “breeders.” The District trade was small until this point, but when cotton planters of the Deep South could no longer get field hands from Africa, the trade in Black human beings swelled exponentially in Washington.

|

An assortment of White slave traders operated from the many tavern barrooms in Washington, D.C., including the slave-trading firm that became the largest in the country for an eight-year period, Franklin & Armfield. By 1830, the capital city served as a depot for the wholesale traders who marched their chained and shackled Africans right past the Capitol, even while the Congress sat in session. One observer wrote, “The auction block, the lash, and the manacled gangs on their way to the Deep South were as much a part of Washington as the steamy climate, the malaria, the marshes, and the dust.”

D.C. Slave Pens and Auction Blocks

The United States government not only condoned the slave trade in the District but also afforded the traders every public accommodation. For 34¢ per day the federal jails could be rented by the traders to house the slaves headed for market. White criminals would sometimes have to wait for accommodations in favor of the more lucrative traffic in Black slaves. In one five-year period in the 1820s, 742 Blacks had been kept at the jails in Washington, not one of whom had been accused or convicted of a crime.

In the Christmas season of 1837, a “free” Black woman and her four young children were torn from their husband and father and locked in the District jail to be held for shipment to the South. Distraught and afraid, she resolved that her babies would not grow up as slaves and proceeded to kill them with her bare hands. Two of her children died before she could be restrained. She was tried for murder and acquitted on grounds of insanity. Her White enslaver returned her to her previous owner for breach of warranty—she had been “warranted sound, mind and body.”

The privately owned slave pens, called “Georgia Pens,” were no less revolting. These jails were the scenes of endless tragedies and gruesome horrors—with full government sanction. One of those dungeons was known as Williams Private Jail (a.k.a. The Yellow House). It was between 7th and 8th Streets, just south of the Smithsonian Institution grounds, not far from the site of the 1995 Million Man March.

Owned by William H. Williams, the jail was described as a three-story brick dwelling, covered with plaster, painted yellow and standing in full sight of the Capitol. (Ever wonder why so many Blacks today are named Williams?) The “Yellow House” enjoyed “a virtual monopoly of the private-jail business.” Williams’ success was so rapid that before the end of 1836 he had purchased two slave ships, named “Tribune” and “Uncas.” In 1841, trader James H. Birch kidnapped and drugged Solomon Northrup, a “free” Black man, before stowing him at the Yellow House and shipping him to New Orleans. In 1850, one observer found a number of children, “kept here for a short time to fatten.” Shortly after, the Yellow House was sold and the purchaser found staples driven into its walls where Blacks were “chained like wild animals.” This horrifying reality represents the true nature of this nation’s origins—and the unfortunate lot of those great Black builders of this nation’s capital who are the very source of the wealth and power of today’s rulers.

(For more on this secret history, see The Hidden History of Washington, D.C.: A Guide for Black Folks at noirg.org)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!