13 year old Jada Williams said harassed for writing essay comparing school to modern slavery

By Jason Muhammad -Guest Columnist- | Last updated: May 2, 2012 - 10:53:04 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Black Youth in Peril: The Narrative of Jada Williams

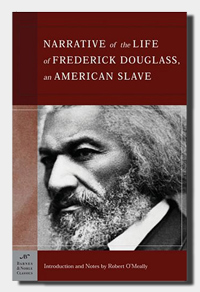

“The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers. I could regard them in no other light than a band of successful robbers, who had left their homes, and gone to Africa, and stolen us from our homes, and in a strange land reduced us to slavery.” -From The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

Jada Williams

|

Jada was recently forced to endure the chastisement of her teachers, principal, and other school administrators for her response to a district-wide activity where students were asked to read The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, and write a brief essay explaining what the narrative meant to them.

Because of the essay she submitted, Jada was forced to leave school and was ultimately transferred to another school in order to protect her from further mistreatment.

Dr. Bolden Vargas, interim superintendent of the Rochester City School District, initiated the voluntary assignment for grades 7 thru 12, to be completed over the holiday recess last December. Students who participated were offered various rewards, including meal vouchers from local grocery stores, and tickets to semi-professional basketball games.

|

Moreover, after escaping from the horrors of slavery, Douglass lived in Rochester, where he played an important role in the anti-slavery abolitionist movement. And it was in Rochester that he delivered his famed 4th of July Speech where he chastised America for the hypocrisy of a day that celebrated freedom, while those who looked like him were enslaved.

Jada composed a powerful essay comparing her own educational experiences with those of Douglass. Like him, she lamented that her peers did not like to read, and how difficult it was to obtain a decent education.

Like all of the students who completed the task, Jada turned her essay in to her English teacher on the first day back from recess in January. According to the girl and her family, the following day teacher Jennifer Robie-Shoemaker approached Jada and stated that she was offended by what Jada wrote.

When Jada asked her why she was offended, Robie-Shoemaker stated that Jada had used the term “White teachers,” according to the family.

Jada says she told Robie-Shoemaker that she was talking about another teacher. Robie-Shoemaker’s response was, “Don’t talk about my colleague like that! Have you ever had a Black teacher? Did she teach you?” according to the young girl.

Jada says she responded “yes,” but felt very uncomfortable and left the classroom.

When Jada returned home that evening, she told her mother, Carla Williams, what happened. Mrs. Williams was left wondering if teachers in the school district had even read the book, or received any professional development on the assignment before it was given.

That evening Jada’s mother said she also received phone calls from the school’s assistant principal, and Jada’s social studies teacher saying the girl was misbehaving in class. The mother says she immediately called for a parent-teacher conference, feeling something did not seem right.

The next day, Mrs. Williams, the assistant principal, Jada’s social studies teacher, the school’s parent liaison, and Robie-Shoemaker met.

“The teacher (Robie-Shoemaker) kept saying that Jada was angry and that something was wrong with her, and that she needed to see a counselor,” Mrs. Williams recalled. “They were trying to make it sound like something was wrong with Jada.”

Mrs. Williams felt nothing was resolved at the meeting. Immediately afterwards she began receiving more phone calls about her daughter’s behavior.

“Teachers that had never called before began calling and saying that Jada was angry,” Mrs. Williams said. “They were using the same language that Mrs. Robie-Shoemaker was using.”

In addition, though all of Jada’s progress reports indicated very good grades, her report card suddenly showed she was failing classes.

Another meeting was called. This time, along with Jada, her mother, the parent liaison, and school principal, Robie-Shoemaker was accompanied by the vice-president of teachers’ union.

“The people from the school kept saying how much they loved Jada,” Mrs. Williams recalled. “But I told them, ‘I don’t need you to love her, I need for you to educate her.’ ”

“The English teacher kept saying that she was so proud that Jada wrote the very way that she taught her to write. So I asked her, ‘If you taught her this, why are you offended by what you taught her to do?’ ”

“I asked her, ‘Did you know that Jada had plans to be an educator in the future? What kind of message are you sending as a teacher?’ ”

It was then revealed that Robie-Shoemaker had made copies of Jada’s essay and circulated them among faculty and staff. When asked why she did this, the union representative said the teacher did not have to answer the question. But Robie-Shoemaker simply replied, “I don’t know,” according to Jada’s mom.

According to Mrs. Williams, when pressed further for answers, Ms. Robie-Shoemaker appeared to become emotional and stated that she could not get the young student’s essay out of her mind. The teacher claimed she was haunted by the words on the page, and repeatedly stated of Jada, “She lumped me in! She lumped me in!” When asked to explain, it was again stated that she did not have to answer the question, according to Mrs. Williams.

Mrs. Williams demanded that Jada be transferred to a different school, though the administration told her there was “no better school for Jada.”

The school district eventually did move Jada, but not to the school requested by Mrs. Williams. On her first day, Jada witnessed four fights at the new school. Soon she was targeted by students who had heard teachers in the building talking negatively about her, and she was threatened with violence.

“I felt like Ruby Bridges,” Jada stated, referring to the little girl who in 1960, at six years old, became a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement in the South when she had to be escorted to school by federal marshals. Young Ruby’s brave act was famously depicted in the 1964 Norman Rockwell painting, The Problem We All Live With.

Mrs. Williams refused to send Jada back, and called school district officials every day, asking to meet with interim Superintendent Dr. Vargas. She says she never heard back from anyone. As a result, Jada was only able to attend school for two days the entire month of February. The school district then threatened to report Mrs. Williams to Child Protective Services, charging her with educational neglect.

“My daughter missed school, but that teacher is still teaching,” Mrs. Williams said.

Jada’s story eventually got out into the Rochester community, and many educational advocates and community activists became involved. The local Black-owned radio station spread news of the story, and a Facebook page was created. Community rallies were called, and there as an outpouring of support for Jada, as the public became increasingly aware of the young student’s plight. In fact, the Frederick Douglass Foundation of New York honored Jada with the 2012 Spirit of Freedom Award for her courageous stance in speaking truth to power.

“I was getting calls from Time Magazine, CNN; they all wanted to talk with me and Jada. But the superintendent didn’t want to meet me,” said the mother.

But then she got a call.

When Mrs. Williams answered the phone, Dr. Vargas greeted her with, “Mrs. Williams, I heard you want to hear from me.”

Mrs. Williams eventually got a meeting with Dr. Vargas March 9, where she said the superintendent told her, “I don’t know education; I just know kids.”

Dr. Vargas then promised to wipe everything clean, and transfer Jada to a very innovative and progressive school, so that Jada could start fresh and once again experience academic success, according to the mother.

But the damage had already been done, and the heart of the matter, the message in Jada’s essay and her perception of the education that she and her peers receive seemed to have been lost.

Adding insult to injury, when Mrs. Williams asked to see her daughter’s cumulative folder, in order to be sure that there was nothing negative hidden in it, district officials could not produce all of the documents. It was further discovered that Jada’s records had been somehow mixed in with another student who had a similar name.

“It’s so much bigger than Jada,” Mrs. Williams said. “You can’t call yourself an institution of learning if you’re hindering that process.”

Though Jada is pleased in her new school, she would like a public apology from the district and school administration, including the principal, the assistant principal, and especially Robie-Shoemaker. She would also like to be a part of developing a plan for professional education for teachers and administrators to have them better serve the needs of children.

“I just don’t want this to happen to anybody else,” Jada said.

(Jason Muhammad is a member of the Nation of Islam in Rochester, New York.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!