Black Folks' Guide to Understanding Christmas

By Alan Muhammad -Guest Columnist- | Last updated: Dec 22, 2011 - 4:44:22 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

Where Did Christmas Start?

Since recorded time almost every agricultural society engaged in some sort of festive end of the year celebration. In Europe, the shortest day of the year, or winter solstice, was the cosmic event that drew the most revelers to the town square, but most everywhere else these activities were related to the period of abundance following the yearly harvest.

|

Saint Nicholas, Jesus, & Racism

Saint Nicholas occupied several peculiar positions in Christian culture including being the patron saint of school children, shipping, and pawn brokers, among other titles. Born in the fourth century in what is now Turkey, his legend would later find its way into America as Santa Claus—a mispronunciation of Saint Nicholas. We can see how they connected him to Jesus by an odd legend that gave him power to raise the dead. According to the story an innkeeper killed three boys and cut up their bodies, intending to sell their remains as pickled pork. Nicholas happened upon the scene, supernaturally sensed the crime and reassembled the bodies and brought them back to life. It was this macabre tradition that may have given him life-restoring parity with Jesus in European minds.

Racism was interwoven in this Christmas folklore through another disturbing tale. Nicholas’ function in the church was to judge the goodness or evil of the children in his domain. He would quiz them on their church lessons, rewarding them with candy and gifts, or chastising them with sticks or pieces of coal. He was accompanied by a sidekick named “Black Pete,” described by one scholar as a “hairy, chained, horned, blackened, devilish monster ... clutching a gaping sack in his hairy claws.” Black Pete’s job was to glare at the children while Nicholas drilled them on their lessons. The menacing monster with African features would every now and again flash his enormous canines and leap toward the frightened children, threatening to beat them with his rod. Nicholas warned the bad children that this “Black Pete” would stuff the little transgressors into his sack only to be released at the next Christmas.

This Wall Street version of “Christmas spirit” has led to a growing Black Christian rejection of this profanation of Jesus’ life. They watch every year as His gifts to humanity are bargained away in favor of the image of a morbidly obese White North Polean idol whose jollity is driven solely by credit card debt.

This punitive image of St. Nick softened over time in Europe and to this day they still hold events around the image of “Black Pete” with White actors in blackened faces wearing brightly-colored clown suits (see photo). It is probably “Black Pete” who is the inspiration for the popular Dr. Seuss tale “The Grinch Who Stole Christmas.”

The practice of giving gifts in the name of Saint Nicholas was frowned upon by the father of the Protestant church Martin Luther who then introduced Christkindlein—a messenger of Christ—as the gift-bringer. Again, through mispronunciation, Christkindlein came to be known as Kris Kringle, a name which is now used interchangeably with Santa.

Coming to America

Though “Black Pete” didn’t make the trans-Atlantic crossing to the “New World” with our chained African forbears, “Santa Claus” reached America in Dutch form along with other unseemly pagan customs. The Massachusetts Puritan Cotton Mather bitterly complained that this imported Christmas tradition mocked rather than honored Jesus: “[T]he Feast of Christ’s Nativity is spent in Reveling, Dicing, Carding, Masking, and in all Licentious Liberty ... by Mad Mirth, by long Eating, by hard Drinking, by lewd Gaming, by rude Reveling...” Often these European immigrants blackened their faces or disguised themselves as animals or even cross-dressed, presumably to maintain anonymity for much ruder acts, and similar accounts of the early Christmases abound including one cleric who decried the transvestitism, the “Uncleanness and Debauchery,” as well as the rampant sexual orgies or “chambering.” Indeed, there was an annual increase in the number of births in the months of September and October. It got so bad that the Puritans actually outlawed Christmas in their settlement in 1659 and fined those who celebrated in any way. The holiday was reinstated in 1681 but not before it was roundly condemned as blasphemous and far-removed from the way of Jesus.

Christmas and Plantation Slavery

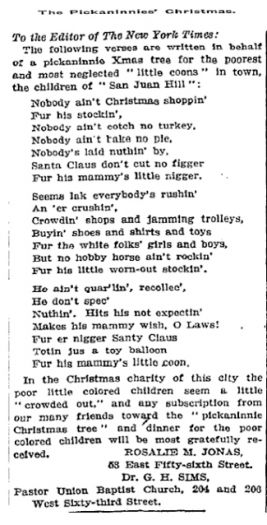

The Plantation South had its own reasons for promoting the Christmas mythology. In order to combat abolitionist rabblerousing slave owners with the help of Northern newspapers promoted an idyllic garden vision of happy slaves enjoying a festive Christmas season. Traditionally, Christmas fell at a time when the end of harvesting idled the workers. The brutality of the overseers temporarily receded and the enslaved Africans came to regard these times as their only respite from the cruelty of plantation life.

They created their own distinctive traditions known by various names including “John Canoeing,” “John Koonering,” or other similar terms. The festivities included singing, dancing, feasting, and dressing up in the White man’s cast-off clothes. The annual merrymaking served planters’ interests who promoted heavy drinking and partying as a pacifying hedge against the always imminent escapes and insurrections. One Georgia slaveowner wrote: “I have seen the jollity & mirth of the black population during the Christmas holidays. Never have I seen any class of people who appeared to enjoy more than do these negroes...”

Selling Out Christmas Yet Again

Just as the early Christian leaders bargained with the truth of the birth of Christ, the burgeoning merchant class in America positioned themselves to make Christmas a bonanza of consumerism and boundless profits, and so Santa Claus was commandeered to be their portly pitchman. Beginning around 1880, advertisers began to encourage the purchase of manufactured rather than homemade gifts. Wrapping paper and Christmas cards were introduced and Christmas bonuses and “Christmas Club” bank accounts promoted the holiday as the season of boundless spending. As The Hon. Elijah Muhammad wrote: “The merchants’ pockets are made fat for Christmas—the tobacco factories, the beer and whisky traffic, and wine ... There is no holy worship on that day for [Jesus].” The fact that the biggest profiteers on Christ’s birthday are Jewish—in whose synagogues the name of Jesus cannot even be uttered—seems to concern no one. Jewish mega-marketers like Gimbels, Macys, Neiman Marcus, Sears, and many others all do their profitable best on this holiest day of the Christian year.

This Wall Street version of “Christmas spirit” has led to a growing Black Christian rejection of this profanation of Jesus’ life. They watch every year as His gifts to humanity are bargained away in favor of the image of a morbidly obese White North Polean idol whose jollity is driven solely by credit card debt. Celebrations like Kwanzaa, with its seven principles that are truly worthy of the name—Unity, Self-Determination, Collective Work and Responsibility, Cooperative Economics, Purpose, Creativity, and Faith—are gradually infusing more substantive meaning into end-of-the-year Black celebration culture. Certainly, Christmas as it is practiced in America is a strange European tradition that has gone out of its way to exclude the Saviour Himself, while generating a massive amount of Black consumer debt, and managing to add a few racist insults on the way. Is this anything that an awakened Black family ought to be involved in? Read the Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s teachings of Christmas (pages 173-81) in Our Saviour Has Arrived.

(Alan Muhammad is a citizen of the Nation of Islam.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!