‘True story of an enslaved man who fought, sacrificed everything for liberation’

By Final Call News | Last updated: Oct 11, 2016 - 3:23:26 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

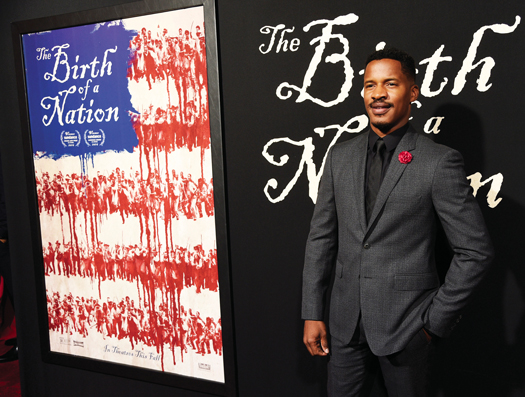

Nate Parker, the director, screenwriter and star of "The Birth of a Nation," poses at the premiere of the fi lm at the Cinerama Dome on Sept. 21, in Los Angeles. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

|

Nate Parker producer, director, lead actor of the film Birth of a Nation was interviewed by Charlene Muhammad, Final Call newspaper national correspondent prior to the Oct. 7 release of the film. The movie covers the life of 19th century freedom fighter Nat Turner and his 1831 slave insurrection. Mr. Parker touched on a range of subjects and controversies during the telephone interview.

Charlene Muhammad (FCN): Your movie on Blacks’ resistance to slavery comes as America struggles with the old, ugly and deadly problem of racism and White Supremacy. What are your thoughts on the original Birth of a Nation and its impact?

|

FCN: What inspired you to make this movie and at this time?

NP: Really, it started off as the absence of heroes. You know, I grew up in a time where what I was learning about the narrative of America was in the context of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, the forefathers that created this country and then “honest Abe” freed the slaves. Nowhere in the narrative was I ever taught that someone that had my complexion fought for the liberation of the oppressed. In fact, I didn’t know that Nat Turner wasn’t the only one, even when I learned about Nat Turner. So, through learning about Nat Turner, I gained access to Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and many who resisted. Through oral history and slave narratives, I learned of those who resisted by breaking tools, who poisoned their enslavers, who ran away, who some led their slave owners into the woods and fought them or killed them. I learned about so many forms of resistance that were just never taught to me. When I had the opportunity to start writing, I said to myself if there’s any story I want to tell, it is the Braveheart-like story of Nat Turner, the true story of an enslaved man who fought, sacrificed everything for a liberation that he would not ever really be able to taste.

FCN: When you sold your film to Fox, did you have to make any content concessions or were any changes made from your original script?

NP: Nope! None. No. Zero. For one, I raised the money, and for two, I had leverage because there was more than one studio that wanted the film. One of the conditions with the film is that it would be shown in its original form, that I would have creative control, that I would have final cut, that there was no quorum, that there was no vote, that I would have the final say on what was actually given to the people for better or worse, and they agreed and without any defense.

FCN: I got the message of the film without having to see Black women’s and men’s bare bodies on that auction block or seeing Sis. Gabrielle Union’s character raped. Was that a conscious decision?

NP: We didn’t have to see it to understand the dynamic. The reality is that when we tell our stories, and when we tell them with the heart of who we are, the humanity of our own personal experiences and what we’ve had to endure even in this century, we understand that we don’t need shock value.

The problem is we so rarely get to tell our own stories, and when people that are outside of the group of oppression attempt to tell the stories of those who are steeped in that oppression, they fall into the tropes that are the low hanging fruit.

Then, because they are so married to the tropes, and they feel an emptiness within the product. They feel they have to elevate the graphic nature to fill those holes, but the reality is I carry in my veins the blood of my ancestors that lived it.

Through prayer, and meditation, and research, I can find those moments of humanity, those moments of desperation, those moments of action that in my opinion can fill all the gaps that need to be filled without any type of gimmick or device.

FCN: Any time in this process did anything just break you down? Made you run home to your wife and say, “Oh my God! This is hard!”

NP: Literally every day. We have 27 days to shoot a schedule that was originally 40 days. That’s why I give all glory to God because every single day was a miracle, and I had to raise millions of dollars for a film that Hollywood said they would never make, because it was about a Black man without any White hero, that it was about slavery, a time that people didn’t want to hear about, that it was about resistance and people didn’t want to deal with the violence, and about overseas, how people overseas didn’t care about Black people.

All these self-deprecating ideas that I just didn’t believe and I just didn’t buy into.

I had to go door-to-door and raise money every day! I had to spend my own money. There’s no reason this film should exist outside the fact that it is ordained.

Like God wanted this film to exist, because there were so many reasons why it wasn’t supposed to happen. Now we have this film and no one can take it away, so it doesn’t matter who’s destroyed in the process. In my opinion, the hope is that this film wakes us all up or at least starts the conversation. We appropriate the feeling of talking about the race without ever having to talk about it. We have these meetings and we say, “Ah man. Things are so bad they just need to,” and then we pivot into something that’s more comfortable. But we don’t have conversations about race, about pervasive racism, about systemic racism, about White supremacy. We don’t have these conversations. We kind of reduce our responsibility to not saying the N-word and to condemning the Klansmen, rather than saying many of our celebrated institutions are systemically racist. Many of our institutions that deal with law enforcement or controlling the bodies of Black people are systemically racist. Many of our educational institutions are systemically racist. Many of our corporate institutions are systemically racist. We don’t have those conversations, so things don’t change. I believe in the power of the moving picture, and if anyone doubts that, look at Griffith’s 1915 depiction of Black life, where he had people in Black face in the White House barefoot, with their feet on the table, eating fried chicken. And here 100 years later, we have a Black man in the White House, not to say these things have been done, but to say that they use propaganda to say if a Black person’s ever in the White House, they will kick their shoes off, kick them under the table, and eat fried chicken. And they will desecrate everything that our forefathers created, when in all actuality, Nat Turner stood for the ideals of America more so than almost any of our forefathers. Many of them had slaves, and many of them very, very clearly and explicitly through their speeches spoke against Blacks as an inferior race in America.

FCN: On the role of the traitor—he winds up being not the house Negro as many may think it would have been, but the young boy, similar to the age of Tamir Rice, Tyree King, those in 20s,’ 30s’ and in their prime being shot today. Do you think that it could send or people could receive a message to those protesting or thinking about joining?

NP: I think that Jasper, the character who you would call the Judas, is our youth, and Nat Turner basically said the least among us can have the greatest impact. When he came to the table and Harp said, he’s just a boy. Nat Turner said, well so was David. We have such a knee-jerk reaction to our young people, not recognizing our young people carry the torch. We condemn them for their hats worn a certain way or their hoodie worn a certain way, or their pants sagging a certain way, but the reality is, we need to meet them where they stand. We need to arm them with what they need to fight, and then we need to get the hell out the way and let them lead. That is something that is not happening in our communities.

The real hero of this movie, on one hand, is Nat Turner, but on another hand, Nat Turner is the messenger and Jasper is the hero. You get what I’m saying? Nat Turner being the messenger of sacrifice and the Bible says a good man leaves an inheritance for his children’s children. Nat Turner influenced, in his rebellion, he had people as young as 13-years-old! He said listen, this liberation belongs to you, too. Any movement that has been successful in this country for Black liberation has included old and young, men and women, and people not of color that understand their superiority complex, that understand White supremacy, and that internalize that, sort that out, and heal from that in order that they might help, because there are some people of color that are not on our side. The hope was that in ending the movie in that way, we would recognize the importance of our young people in the fight for justice, that Trayvon and Tamir could have been the geniuses that had solutions that could have liberated our people but their gift was taken from us before it could grow. If only we recognize the power that comes from the message. When we dilute the message, or, as Carter G. Woodson says, we miseducate, then the thinking around that miseducation is more destructive than the pervasive racism itself. Carter G. Woodson says in the “Miseducation of the Negro,” if you control a man’s thinking, you don’t have to worry about his actions. You don’t have to tell him to go to the back door. He’ll go on his own. If there is no back door, he’ll cut one out for his own pleasure. We need to change the way we think in this country, and if my film could be a device for that, then praise the Lord, because I’m not making a film for a weekend. I’m making a film for a legacy.

FCN: The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan says it’s not what the enemy knows. It’s when he knows it. What are your thoughts about the timing of the release of your film about the untold numbers of rapes of enslaved women, men and children and the media’s sticking you to the wall over that?

NP: The reality is this: the Lord is my light and my salvation. Whom shall I fear? The Lord is the strength of my life. Of whom shall I be afraid? When the wicked, even my enemies and my foes came against me to eat up my flesh, they stumbled and fell. This is kingdom business. Our people, let’s not be distracted. The reality is Nat Turner’s bigger than me or anyone else. The legacy of Nat Turner, what he did, standing. There would be no America if there was no rebellion. And guess what? We’re not talking about Thomas Jefferson and his behavior. God is just. If God is who we think he is, and we are celebrating, and praising, and give glory to, then something is upon us if we don’t change.

FCN: Thank you.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!