Don’t be fooled: Latino = Indigenous

By Santy Quinde Baidal Indian Country Today Media Network | Last updated: May 1, 2014 - 5:33:15 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Indigenous people from all parts of Mexican state of Oaxaca, wearing traditional clothes and artifacts, in a celebration known as Guelaguetza. Photo: Wikipedia.org

|

Late last night, my father and I talked about how the ethnic term Latino mislabels Indigenous and mixed-Indigenous people from Mexico, Ecuador, Puerto Rico, etc. For a long time, we believed Latino and Hispanic correctly defined the Spanish-speaking mixed-Indigenous and Indigenous people in Latin America.

As we crossed the George Washington Bridge, I wondered, Why is this so? I mean it’s true. We do speak Spanish and we practice Spanish culture. But we also come from a land that is still governed by our Indigenous relatives. I thought hard about how to politely counter argue his belief. His opinion. His Latino identity.

|

He laughed at me. He said, “They are Asians, though. You can’t confuse their race with Spanish.”

“Exactly, so why are we the only ones considered Latino or Hispanic? Some of us are Indigenous, right? Think about it, papa. We are Guayakos and Manabítas. We come from family clans that stretch back for thousands of years of Indigenous tradition.”

“Well..” he stammers, “I would say, we’re Ecuatorianos.”

Latino or Hispanic is a term coined by the United States to identify Spanish-speaking people coming from south of Mexico. The reality is Spanish-speaking people from Latin America come from a variety of racial and cultural backgrounds. We are like a rainbow.

However, since 2011, Latinos or Hispanics now start to identify as Native American, the Census shows. Even the New York Times features their article on the cultural change and perspective of Indigenous identity among mestizos, mulattos, and Indigenous people.

Also, Latino comes from the root word Latin which corresponds to the nations that used to form the Roman Empire: Spain, Portugal, Romania, Italy, and France. According to El Boricua, “The word Hispania thus refers to the people and culture of the Iberian peninsula, Spain in particular. The term Hispano (Hispanic) later was used in referring to Spain and its subsequent New World – New Spain, conquered territories which covers most of Latino America.” The White-mestizo society or descendants of Spanish relatives can claim these labels to themselves.

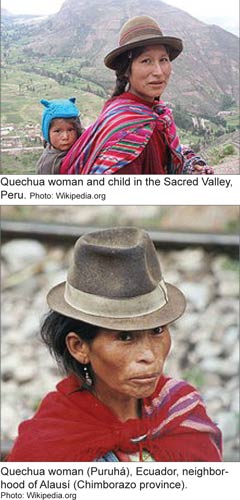

But Latino is not a person who only looks Mexican and speaks Spanish. Many of us come from mixed-Indigenous heritage and some of us are Indigenous, too. For example, Ecuador is home to 30-plus Indigenous nations and a home to 8 million descendants of the Quitu-Shyri and Spanish ancestry. It’s also home to 1 million Euro-Ecuadorians and 1.3 million Afro-Ecuadorians. However, the 8 million Ecuadorian mestizos form part of the rainbow colors of the Indigenous race mixed with the Spanish and the African cultures. In Ecuador, we say “tenemos la pinta ecuatoriana” (we have the Ecuadorian look) because some of us are brown, have black hair, and some, more than others, inherit the Atahualpa face, our last Tawantinsuyu King in 1535. We also dance to merengue and reggaeton, but we blast Indian music and do the round dance, stomp the floor, swing the skirts, and chirp like the Curiquingue and Quinde birds.

Ecuadorians make up the majority of mixed-Indigenous and Indigenous population, among other groups like Afro-Ecuadorians and Euro-Ecuadorians, who re-invent a fusion of all cultures, languages, and religions, yet preserve their Indigenous ethnicity, traditions, and roots simultaneously.

The Idle No More Movement is an excellent example of how Indigenous people in North America unite to stand up and fight for their culture, land, and identity against a people who think it’s okay to walk over Indigenous people with mascot names and Halloween Indian costumes. I also think the Idle No More Movement should include Indigenous people and mixed-Indigenous people from Spanish-speaking nations as an effort to collaborate, unite, and support one Indigenous people across both continents.

Do we call an African-American a Britannic because he or she speaks English? Do we call an Arab an Amish because he or she looks White? Why don’t we call Euro-Americans “mixed” or “mestizos” because they also have Irish, Italian, German, African, and Indigenous blood, some more than others? However, there is no debate about our differences. We come from different nations, backgrounds, religions, cultures, and so forth. But the key point is to co-exist in peace and respect each other. The principle is to not step on people’s sacred space without asking their permission. The Indigenous space has been repeatedly trespassed and disrespected in the Americas.

I can only speak of what I‘ve seen in Ecuador. In Ecuador, the label Mestizo provides an opportunity for Indigenous people to climb the social ladder. In order for them to not be hated, insulted, harmed, put down, ashamed, physically assaulted, and to some extent, massacred in ethnic and cultural genocides, the ethnic label “mestizo” provides a convenient strategy to avoid all of the aforementioned complications. However, Indigenous people should not feel obliged to make the switch from Indigenous to Mestizo because of the shame with their Indigenous identity. Their culture is as beautiful as that of the African-American, European-American and Asian-American.

In Santa Elena, Ecuador, we identify as Indigenous people. We go by “cholo comunero,” and some, more than others, by “Wankavilka” to emphasize their ethnicity. The Ecuadorian government sends us a census that provides three options: White, Black, and Mestizo. We are forced to put mestizo even though in our hearts we know we are Indigenous to our ancestral lands and cultures, but this mislabel affects new generations of youth who start to distance themselves from their Indigenous heritage and encourage outsiders to expropriate our lands because we do not “voluntarily” identify as Indigenous (Original Source in Spanish). Therefore, in this case, the mestizo concept does not equally glorify two cultures, but only the dominant European one. It serves to disenfranchise Indigenous people in Latin America. In a parallel comparison, there are Latinos, (Indigenous Spanish-speaking people from tribal nations in Latin America who migrate to the United States), who do not want to identify as Latinos and Mestizos but are forced to because it’s the only option.

Appropriating a local tribe that is not yours is also NOT the respectful manner to go about this either. However the U.S. census should provide an ethnic label that speaks for Mexican, Central, and South American Indigenous people. This also gives an opportunity for mixed-Indigenous people to learn from their culture via Indigenous groups in United States settings. Because as mixed-Indigenous people from Spanish-speaking nations, we have a right to learn about our Indigenous past that includes everything before 1492. Our nations started way before the colonial contact.

Imagine what would happen if mixed-Indigenous or Indigenous Ecuadorians, Mexicans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Peruvians, Bolivians, among other Spanish-speaking nations re-identify with their Indigenous roots. How would that cause a chain reaction in Latin America and how would that redefine our culture, our history, and our thought process?

Santy Quinde Baidal, blogger of The Quinde Journey / Wankavilka Nation (www.squinde.wordpress.com), speaks about his experience of re-identifying with his Wankavilka Comunero Indigenous identity as an Ecuadorian-American citizen in the United States. Thanks to oral tradition and extensive independent research, Mr. Baidal learns about his Indigenous culture, identity, and traditions that stretches back to 12,000 years, to the first people of Santa Elena, Ecuador.

Related news:

Hispanic, Latino, or Indigenous (FCN, 10-23-2009)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!