Twenty years after L.A. riots, change is hard to measure

By Thandisizwe Chimurenga | Last updated: May 7, 2012 - 1:48:36 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

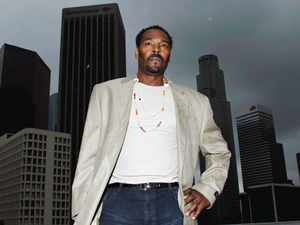

On April 13, Rodney King poses for a portrait in Los Angeles. The

acquittal of four police offi cers in the videotaped beating of King

sparked rioting that spread across the city and into neighboring

suburbs. Cars were demolished and homes and businesses were

burned. (AP Photo/Matt Sayles)

|

With the 20th anniversary of the event came a simple question: What, if anything, has changed for Los Angeles and America?

For Karen Bass (D-Calif.), “tremendous progress” has been made, “yet work still needs to be done.”

According to MarketWatch, produced by the Wall Street Journal, metro Los Angeles’ current unemployment rate of 11.1 percent is “higher than it was when the violence and destruction broke out … a roughly 40 percent increase in the jobless rate in 20 years.”

A University of Southern California study after the unrest found Blacks and Latinos in South Central and Southeast Los Angeles suffered from “very high levels of poverty and unemployment. In South Central, 31 percent lived below the poverty level, and the unemployment rate was 13.7 percent.”

The Los Angeles Urban League reported last August that the unemployment rate for Blacks stood at 16.3 percent; while joblessness was 12 percent for Latinos and 8.7 percent for Whites. The poverty rate for Blacks in 2010 had dropped to 21.5 percent, but the median household income for Blacks ($49,000) was 57 percent of Whites’ median income of nearly $86,000.

Before order was restored, 55 people were dead, 2,300 injured

and more than 1,500 buildings were damaged or destroyed. (MGN

Online)

|

Violence, poverty and joblessness helped drive Blacks from South Los Angeles. The Black population is about 30 percent today, down from 50 percent in 1992, according to the Census bureau. Meanwhile there has been a sharp increase in Latino immigrants who now make up more than 60 percent of South Los Angeles’ population.

In a media statement, Rep. Bass said one of the “bright lights” to come from the ashes “was the number of social justice pioneers who were determined that once the smoke cleared, South LA would be a different place—safer for children with more economic opportunities for families.”

Rep. Bass, whose 33rd congressional district encompasses much of South Los Angeles, entered national and state politics after co-founding the Community Coalition, dedicated to advocacy on behalf of South Los Angeles residents, two years prior to the unrest. After April 29, 1992, the organization successfully spearheaded an effort to rebuild South Los Angeles without many of the notorious liquor stores that once littered the landscape, working to replace them with businesses such as laundromats.

Kokayi kwa Jitahidi, a lifelong resident of Los Angeles, also acknowledged the number of non-profit organizations that emerged after the unrest, characterizing the groups as “an explosion” that either provided services or did community organizing. But he also noted a drawback, saying the landscape had become “very top heavy, top layered,” with many of the organizations producing a handful of dynamic leaders.

“What has consistently been the problem is that South L.A. has struggled to build a base of leadership beyond a small core of people,” he said. “What that has done is its really hurt South L.A., particularly Black folks, in our ability to maximize our advocacy to transform conditions.”

Standing at the corner of Florence and Normandie commemorating the “flashpoint” of L.A.’s civil unrest, Skipp Townsend, a former gang member turned intervention worker, seemed to echo Kokayi’s words.

“More leaders who have come out of my age group, where we didn’t have any at first; all the leaders we had were negative. Back in my era, prior to 1992, if you had the drugs, the guns or were the bully in the community (you were the leader); all the leadership was negative for the community. Nowadays, each neighborhood has someone who does intervention, who brings peace. Either they do mentoring, they help to get jobs, they do something, and they’re from the grassroots community, that’s the important part.”

Mr. Townsend noted the crime rate—specifically the number of homicides—in South Los Angeles has dropped. “People my age feel comfortable although my children don’t, but they don’t remember the 1000 homicides (per year) that we were having during that time,” he said.

The drop in gang crime is a tangible example of change for the positive since 1992. Many attribute that change to the “truce” declared between L.A.’s infamous Crips and Bloods who had been “warring” with one another since the mid- to late-1970s.

According to Alex Alonso, creator of streetgangs.com and widely acknowledged as an expert in the study of gangs, one thing that has unfortunately remained the same are the actions of police.

“I don’t really think race relations have changed significantly. I still think law enforcement is overly aggressive towards people of color. More work needs to be done in that area, especially where we have officer-involved shootings against unarmed individuals. There aren’t as many as there were in the ’80s and early ’90s, but it’s still way too many for a law enforcement (agency) that claims to be the best law enforcement in the country.”

According to Mr. Townsend, LAPD command staff now have a policy of building relationships with the community, “which didn’t exist before.”

Vicky Lindsey, an intervention worker and founder of Project Cry No More which focuses on victims of violence, said things have improved between the community and law enforcement. But, she said, some officers still have the same racist mentality. “If we change policies, procedure and laws, that’s fine, but if we don’t change the mentality of individuals, those things don’t make a difference,” she said.

Any discussion on race relations, Los Angeles, its police department, and the Black community in the aftermath of April 29, 1992 is incomplete without the voice of the Korean American community.

According to New America Media, a national collaboration of 2,000 ethnic news organizations in the U.S., “a report in the Korean-language Korea Daily in Los Angeles notes that much of mainstream media’s coverage of the anniversary of the 1992 Los Angeles riots has ignored the impact of that event on the Korean community. Citing local broadcasters’ coverage of the anniversary, the paper points to what it describes as an almost exclusive focus on the African American community, despite the fact that Koreans were some of the hardest hit by the violence and looting that erupted.”

At UC Riverside, a consortium was held to mark the experience of the Korean American community, which lost approximately 3,000 businesses during the unrest. “Sa-I-Gu” stands for the date 4-29 and according to Edward Chang, a professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California in Riverside, “Prior to the riots, Korean Americans were unknown, invisible and unrecognized in American society. After Sa-I-Gu, Korean Americans became active in city politics and proactively involved in multiethnic and multiracial coalition building in Los Angeles.”

Leadership Development in Interethnic Relations, a joint project of the Asian American Pacific Legal Center, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the League of United Latino American Citizens, was created 1989. Its mission to provide conflict resolution and human relations training to alleviate tensions before they explode took on added urgency after the unrest.

Carmen Morgan, LDIR’s executive director, said 10 years after the unrest, she still felt hopeful about the promise of improved race relations. Now, 20 years later, she believes that promise and opportunity has been lost. “And I think that 10 years from now, if we don’t correct our path, where we are now, we’ll be right back where we were in 1992, and with justification,” she said.

While there is good work going on with some genuinely interested in building bridges, “the same complicated dynamics exist … . communities are still separate and distinct, and they still rub up against each other in the same tension-filled ways that they did back in the late ’80s and early ’90s. There’s an awareness and a sensitivity but I don’t think that the underlying root issues have not gone away, and we just need one issue, one spark for that to come to the surface again. I don’t think that the Black community is the epicenter of all tension, the structural racism we are dealing with is at the epicenter of these tensions,” she said.

Min. Tony Muhammad, a resident of Los Angeles since 1995, believes that Blacks in South Los Angeles should follow the example the Korean American community took after the unrest.

“The Hon. Elijah Muhammad said we need a separate state or territory. I have been asking lately in Black Los Angeles, where is ‘Afrika Town?’ Korea has a town … and they have become so economically powerful that they influence politics and they don’t have the largest population. And that’s something we have not yet tried … that’s where we’re failing. We must pool our resources together and become strong economically and then, I believe, we can begin to resolve some of the issues of joblessness, not owning homes, we can give ourselves loans, we can have our own banks, car dealerships, grocery stores, farms. We have not tried that and I believe if we do that step … we can dig ourselves out of the ditch we’ve been pushed into.”

Professor Vernellia Randall said despite the 20 years since the Rodney King beating, very little has changed with regard to policy abuse and brutality in the country.

“I actually think things are getting much worse. You can’t hardly go a month without there being some police brutality. I think you don’t see the beatings, the beat down that Rodney King (got) quite as much although that still happens. What you get more of is the shooting of unarmed people,” said Prof. Randall, a law professor at the University of Dayton.

Professor Randall also said the criminalization of Black children, as evident in recent cases in which five- and six-year-old youngsters have been handcuffed by police is a big concern.

“We’re finding more and more Black children are being tried as adults and we’re finding the police being called in by the school for children as young as six-years-old and them being carted off to jail for temper-tantrums,” added Prof. Randall.

“If you narrowly define the problem as the beating (of Rodney King) those still are fairly rare but if you define the problem as police disrespect for Black lives then that’s really gotten worse,” Prof. Randall told The Final Call.

Prof. Randall is not optimistic about the state of race relations because the country has moved toward dealing with race issues as individual episodes, instead of dealing with individual flare-ups as symptoms of a bigger problem.

“When you deal with episodes you never really deal with getting rid of the problem or changing the law or putting more regulations. You just deal with each little town, each little group, each little thing that happens … people want to believe the episodes represent just a bad cop or a bad whatever. It doesn’t represent the fundamental problem with the system,” said Prof. Randall.

When asked if 20 years from now race relations or issues with police brutality and police shootings of unarmed Blacks will improve, Prof. Randall doesn’t offer much hope.

Until police are held responsible and accountable for their actions, even with their tough job, the problems will continue, she said.

“Your job should require you to know the difference between a person pulling a gun and a person pulling a phone and if you can’t tell that difference you don’t need to be on this job. We’re always talking about zero tolerance. Why don’t we have zero tolerance for police killing a person that’s unarmed?” asked Prof. Randall.

(Final Call staffer Starla Muhammad contributed to this report.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!