Activists want ex-cop accused of torture jailed and police torture outlawed

By La Risa R. Lynch -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Jun 12, 2010 - 1:28:43 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

Mr. Cannon, 59, felt justice slipped through his fingers when federal prosecutors announced in 2008 that a former Chicago police commander who allegedly created a torture chamber at Area Two and Area Three police districts on Chicago's south side was being charged with lying.

Former police commander Jon Burge would not face charges for his alleged role in having two city police officers place a shotgun in Mr. Cannon's mouth, pulling the trigger three times in a mock-execution.

Mr. Burge would not face charges for his alleged part in having officers cattle prod a then-32-year-old Cannon in the genitals while in the backseat of a police car. Mr. Burge would not face charges for other alleged acts of brutality, including smothering suspected murders with a typewriter cover, burning some on a hot radiator or just simply beating confessions out of men held in police custody.

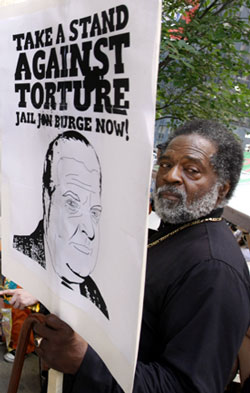

Dardy Tillis of Chicago participates in a rally outside Chicago's City Hall against alleged police brutality and torture under retired Chicago Commander Jon Burge May 24, in Chicago. Jury selection was beginning in Mr. Burge's federal trial where he is accused of lying about the long-ago torture of suspects. Photo: AP/WideWorldPhotos

|

During his murder trial, Mr. Cannon testified about his torture, but his claims were dismissed as desperate fabrications. The courts equally rejected similar claims from other Burge torture victims. In all, Mr. Burge and his underlings allegedly tortured 110 men from the 1980s until the police department fired him in 1993.

For Mr. Cannon, Mr. Burge's perjury trial is a slap in the face.

“I'm not happy about it,” said Mr. Cannon who believes Mr. Burge is getting off with a wrist slap. “I'm not enjoyed with Burge going on trial for anything of this magnitude. It should have been greater and should have been long before now. I hope people don't get complacent, thinking that this is the beginning of the end, because it is not.”

Mr. Burge faces two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury after testifying he did not use or know about the use of torture during a 2003 civil rights violation case. If convicted he faces 45 years in prison.

Justice, Mr. Cannon contends, won't be served until other detectives under Mr. Burge directly involved in the torture are indicted. Those include Mr. Cannon's alleged torturers, former officers John Byrne and Peter Dignan who both have been accused of torture and abuse in 13 other cases.

|

‘In the state of Illinois, there is no statute that criminalizes acts of torture by police officers. It is noteworthy, however, that there is legislation that criminalizes the torture of animals. We think there should be such legislation when law enforcement officials abuse their badge and torture individuals in their custody.’ —Joey L. Mogul, ICAT member and an attorney for the People's Law Office. |

Mr. Cannon has a pending suit against Mr. Burge and Mayor Richard M. Daley in his torture case. Mayor Daley was then the Cook County state's attorney when allegation of police torture first surfaced.

Making police torture a crime

Grassroots community activists who toiled for years to expose the Chicago Police Department's dirty little secret also contend Mr. Burge's perjury trial falls short of justice. They are seeking tougher measures. They want to make torture by law enforcement officials a crime in the U.S.

The Illinois Coalition Against Torture, a broad coalition of community groups, are pushing city, state and federal officials to enact laws that criminalize police torture. ICAT also wants laws to remove statutes of limitation that prevent police torture victims from filing criminal charges. Mr. Burge is not facing more serious charges because the statute of limitation ran out.

The group also wants new trials for 23 men wrongfully convicted based on coerced confessions. They contend using those confessions violate state and federal laws.

“In the state of Illinois, there is no statute that criminalizes acts of torture by police officers,” said Joey L. Mogul, an ICAT member and an attorney for the People's Law Office. The People's Law has been a stalwart in investigating and representing police torture victims.

“It is noteworthy, however, that there is legislation that criminalizes the torture of animals,” she added. “We think there should be such legislation when law enforcement officials abuse their badge and torture individuals in their custody.”

Anti-police torture advocates hope legislation Congressman Danny K. Davis is drafting will give torture victims the redress needed to bring their abusers to justice. However, it is too late for Burge victims since the proposed legislation is not retroactive.

Rep. Davis's legislation would make torture by law enforcement a federal crime not bound by a statute of limitation. The legislation uses the United Nations' definition of torture to set a standard on what constitutes torture. The UN defines torture as any intentional infliction of severe physical or mental pain.

While there are laws protecting individuals' civil and human rights, there are no laws — state or federal — against police torture, Mr. Cannon's lawyer Flint Taylor explained.

Laws do not differentiate between a police officer punching someone or “electro-shocking some person to an inch of his life,” said Atty. Taylor, also with the People' s Law Office.

He explained both crimes under state law are considered battery and have the same statute of limitation of three years. Torture, as a federal offense, would be a violation of someone's constitutional rights, Atty. Taylor added.

“What we are trying to do here is have federal and state governments recognize torture by police as a more serious crime,” he explained. “The crime of torture should be treated quantitatively different in terms of punishment and in terms of statute of limitation.”

Mr. Burge got away with torture because he covered it for so long, while Mayor Daley, who was the prosecutor at that time, did not prosecute despite mounting evidence that surfaced that torture under Mr. Burge's command was systemic, Mr. Taylor added.

“If Burge had not come forward in a lawsuit and lied about torturing people, he wouldn't be charged at all,” he said.

Mr. Burge's perjury trial was precipitated by a civil rights case against him and several police officers brought by former Illinois death row inmates, including Madison Hobley, who were pardoned by then Gov. George Ryan. Mr. Hobley, also an alleged Burge torture victim, was on death row for a 1987 arson that killed his wife, child and several others.

Removing the statute of limitation would be a deterrent to future Burges said attorney Standish Willis, founder of Black People Against Police Torture. His group also has worked tirelessly to expose police torture and police brutality.

“I think that it will always be a deterrent because then we would start pressing local officials to prosecute under that law, and they can't get away by saying, ‘Well, it is too late. We can't do anything,' ” he said.

Mr. Cannon also believes torture should merit the same credence as arson or treason, which have no statute of limitation.

“There should never ever be a statue of limitation on torture,” added Mr. Cannon, who said adjusting to life after prison was difficult. “It has been very trying, but I have finally adjusted to being back in the free world again.”

A movement for justice

Efforts to create a police torture law and bring Mr. Burge to some semblance of justice grew out of grassroots activism among progressive Whites and Blacks working together to expose police torture.

A 1989 civil rights case brought by a cop killer sparked the groups' convergence. Andrew Wilson was charged with shooting two gang crimes detectives in 1982. His confession, however, was coerced. Atty. Taylor's law office represented Mr. Wilson who testified that Mr. Burge electroshocked his ears with a hand-cranked electric device and burned him on a radiator.

That testimony prompted a police department investigation while a diverse group of community activists began demanding Mr. Burge's firing. Activists soon began to rallying behind other alleged Burge victims, known as the Death Row Ten.

While progressive Whites in the legal community galvanized around the issue, the Black community was slow to catch on even though Mr. Burge's alleged victims were predominately Black.

Atty. Willis noted there was no sustained organizing movement within the Black community around police torture until he created his group in 2005. Additionally, police torture was not on the agendas of the city's leading civil rights agencies, like PUSH, NAACP or the Chicago Urban League.

“Periodically something would come up, and they would speak out, but none of them had sustained programs or organizations dealing with police violence,” Mr. Willis said, noting that even fewer Black attorneys dealt with civil rights work.

The absence of Black involvement didn't mean they were not concern, Mr. Willis explained. There just was no vehicle to mobilize them, he said. His group gave Blacks a way to get involved and raised issues not considered by other groups.

His group was the first to call for reparations for Mr. Burge's alleged victims and cited Chicago's own human right violation with the Burge case as reason not to bring the 2016 Olympics here.

“You need a Black political organization that has the ability and understands the importance of being able to coalesce with other groups … when we think it is appropriate,” he said.

The momentum further gained steam when the human rights and the anti-death penalty movements joined forces. Together, they successfully pressured Gov. Ryan to impose a moratorium on state executions in the late 1990s. He later emptied death row in 2003 after compelling evidence showed several men may have been put there because of Mr. Burge's alleged interrogation tactics.

“The two groups came together in common fight … because there were men who were tortured on death row so it became a unified struggle,” Atty. Taylor explained.

Gov. Ryan commuted death row prisoners to life sentences and pardoned four men—Mr. Hobley, Aaron Patterson, Leroy Orange and Stanley Howard—based on innocence because they were tortured into making false confessions. They won a $19.1 million settlement in their civil rights case.

“That was another victory for the grassroots movement,” Atty. Taylor said.

But the victory was bittersweet. The special prosecutor activists urged to be appointed to bring charges against Mr. Burge refused. The special prosecutor, then Cook County States Attorney Richard Devine, had ties with the Daley administration.

“He spent fours year investigating and refused to bring any indictments, refused to recognize the racist aspect of the torture and refused to call it systematic,” Atty. Taylor said.

“The grassroots movement was outraged that this special prosecutor who was so closely connected to the Daley machine and to the police had written a whitewashed report,” he added.

Undaunted activists wrote a shadow report outlining the extent of alleged Burge and police department crimes. Nearly 200 community groups signed onto the report, which demanded hearings at the city, county and federal level. Eventually that lead to the U.S. attorney indicting Mr. Burge in 2008 and investigating others under his command.

The movement's efforts garnered international attention, when activists presented their findings in 2006 to the UN's committee against torture. The UN's rebuke was resounding.

“The United Nations in their report talked about Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay and Chicago,” Atty. Willis said. “I think that was enough to push the justice department to say, ‘Look! What's going in Chicago? Take care of this.' Right after that Burge is prosecuted.”

Atty. Taylor called the journey to get Mr. Burge indicted an uphill battle that many felt wouldn't see the day Mr. Burge got fired, let alone indicted or even some of his victims pardoned.

“These are uphill battles that would not have been able to be accomplished without a combination of the legal and the activist movement,” he said.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!