Caught In The Crossfire— Black, Blue And Called To Protect And Serve

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- | Last updated: Aug 10, 2016 - 11:57:41 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

A protestor holds up a sign in front of Baltimore police officers guarding the department’s Western district police station during a march for Freddie Gray, April 22, 2015, in Baltimore. Gray died from spinal injuries about a week after he was arrested and transported in a police van.

|

Black police officers are often caught between White peers accused of police violence and criminality while trying to protect and serve their own communities. In some instances Black officers remain silent, willing and active participants in mistreatment and abuse Black communities are all too familiar with.

Amid distrust and dissatisfaction, Black police activists work knowing they are often struck by their community’s righteous indignation over police killings and excessive force from racist or rogue cops.

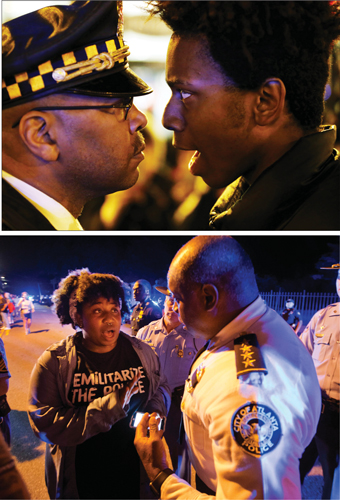

Lamon Reccord, right, stares and yells at a Chicago police officer “Shoot me 16 times” as he and others march through Chicago’s Loop, Nov. 25, 2015, one day after murder charges were brought against police officer Jason Van Dyke in the killing of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald. (Bottom) Protester Aurielle Marie, left, talks with Police Chief George Turner outside the home of Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal during a march through the Buckhead neighborhood against the recent police shootings of African Americans, July 11, in Atlanta. Demonstrators gathered for a fi fth consecutive night, blocking the road outside a mall in Buckhead before marching to the governor’s mansion, where they were staging a sit-in.

|

Some told The Final Call that while they feel key to curbing police shootings and beatings, they are caught in a crossfire as targets of racism, hatred, and police criminality—within the departments they serve.

Rochelle Bilal of Philadelphia at National Black Police Association meeting last year. Photo: Facebook

|

“It becomes a bullying effect where you are targeted, ostracized, and sort of like shunned to the side, because they consider you not a blue brother or sister. But I’m saying there’s no such thing as blue, because you’re African American, or you’re Irish or Hispanic, but blue is the uniform you wear,” Ms. Bilal said.

According to Blacks in Law Enforcement of America, the Memphis Police Department threatened to demote officers who complain about racism.

The non-profit organization reported on its website that Memphis police officials said Black cops would be forced to pay back money they earned after receiving promotions, if they do not back down from claims against the department.

The organization accuses the Memphis Police Department of decades-long history of racism and discriminatory practices against Blacks on and off the police force.

It reported that in recent decades, Black officers charged they were deliberately passed up for promotions while on the job longer and enjoying better records than others who were promoted.

Blue has nothing to do with who cops are as people, it’s a job they do, so cops need to stop saying they’re all blue, Ms. Bilal said.

“I know that there are police that are good-hearted, honest working folk, but if we good-hearted, honest working folk don’t begin to speak up about those that got issues, especially with us, then we are settling for all of us to be looked at as not good people,” she said.

The role and duty of Black cops

Damon Jones has been with the Westchester County Department of Corrections in New York for 27 years. He’s also a law enforcement activist, and the New York representative of Blacks in Law Enforcement of America. He points out the predicament of Black cops dates back to a time when Blacks weren’t allowed to make arrests.

Black patrolmen were ushered in through the Chicago-based African-American Patrolman’s League, the first Black law enforcement organization that worked to raise the level of respect of Black officers, said Mr. Jones.

They understood then Black officers would never be fully part of the racist system, but they were going to protect their community, he explained. “In those days, they weren’t allowed to police anywhere else but in their community, and they couldn’t even arrest a White person, so why not come and keep your community safe?”

Police officers arrest activist DeRay McKesson during a protest along Airline Highway, a major road that passes in front of the Baton Rouge Police Department headquarters, July 9, in Baton Rouge, La. Protesters angry over the fatal shooting of Alton Sterling by two White Baton Rouge police officers rallied at the convenience store where he was shot, in front of the city’s police department and at the state Capitol. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

|

As head of the African American Police League, she tried to address the concerns of officers who experienced conflicts. Her experience was not the norm. She didn’t feel any conflict.

“It seemed to me, and this is what I think the Black community should be challenging these Black officers on, is that there should be no conflict,” Ms. Hill said.

“We’re kind of giving these officers a pass on this explanation of, ‘You know. Wow! It’s really hard being the police because my White counterparts, they don’t understand,’ ” Ms. Hill continued. “If you weren’t the police, your White counterparts would not understand, so would you have a conflict then? And I think the conflict arises when you are trying to straddle the fence.”

The Black community should have a problem with Black officers who care about what White communities or officers think, because that’s not their purpose, she said.

“When White officers become the police, do you really think they care about what the Black community thinks?” Ms. Hill asked.

Such misplaced concerns amount to worrying about promotions, she said.

“That is why the Black community has to get strong with Black policemen. You don’t blame them for things, but you’ve got to give them that support to let them know that we know you became a policeman to protect and serve us. Put that in your head. You did not become the police to go along to get along,” said the outspoken Hill.

Personal challenges and triumphs

Ms. Hill was challenged as chair of a leading advocacy organization for Black police officers, which at one point, was called the Black Panthers of the police department. She had a stigma attached as a woman standing up against the police department’s status quo. These were her greatest challenges because she entered the police force in the early 1980s under then Mayor Harold Washington.

Malik Aziz after the Town Hall “Building on the Future with Our Youth” at the National Urban League of Greater Atlanta. Photo: Facebook

|

There weren’t really a lot of problems on the streets with White officers because Whites understood the Black community was in sync with the Black officers, she said. When Mayor Washington died, things reversed, the strong Black city council was led back to the plantation, and many Black officers even became weak, she added.

“The White police department had started to turn White again. They started to resurface, so they came after the League. They came after me. I mean my pictures literally made the wall of the men’s bathroom in places that I worked,” Ms. Hill recalled.

Today’s community violence problem stems from weak Black officers who began acquiescing to the whims of racist White officers, she said.

The day she walked into the police academy at 29, Ms. Bilal realized racism existed in the institution she had decided to join.

In one incident, a White officer was allowed to determine which driving car she wanted, while Ms. Bilal was not. She was recommended for termination by a training supervisor but a Black male sergeant investigated things and told her she was going nowhere, Ms. Bilal said.

According to Malik Aziz, national chair and executive director of the National Black Police Association and deputy chief of the Dallas Police Department, people want to understand how officers balance the contradictions. “They just want to know how you are a member of a police organization that has, whether it’s real or perceived, done so much harm in communities of diversity or communities of color,” Mr. Aziz noted.

Blacks in law enforcement have historically fought to diversify police departments but have had to operate under a system that’s not so good, he observed.

“That’s why we experience problems today, because for Black people, we see it was very real and it happened yesterday, not 30 years ago or 40 years ago. It’s very real in the minds of themselves, their parents, their grandparents … to see dogs or water hoses,” Mr. Aziz said referring to police violence.

According to Mr. Jones, the triumph for Black officers is always working with their community, those victimized by alleged police crimes, and trying to help them find justice.

Triumph also comes from getting the respect from the community because Black officers often get kudos from people in the streets who know they are cops, and will stand up for their community, Mr. Jones said. A lot of blowback comes from inside the police departments or institutions, he continued. There has been name calling and attempts to ostracize him. After 27 years on the job, he’s used to it.

Heroes not traitors

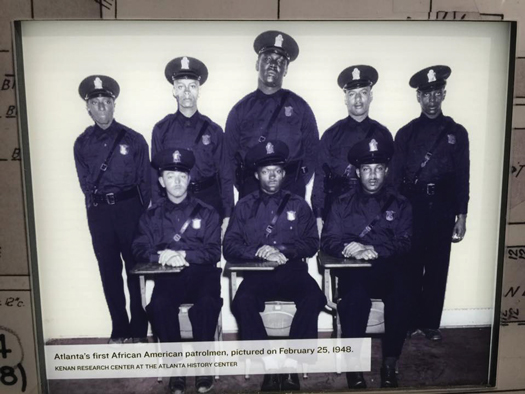

Atlanta’s first Black police officers photo from 1948 displayed at Atlanta History Center. Photo: Facebook/Malik Aziz

|

The national discussion about how to address problems between police and Black communities includes calls for more Blacks on police forces. But there are specific efforts to keep the numbers of Blacks down, according to Ms. Bilal and others.

In Philadelphia, Ms. Bilal charges police officials implemented policies to block Blacks from joining police ranks. Under former Police Commissioner Charles H. Ramsey, who is Black, applicants were required to have at least 60 college credits and a valid driver’s license for three years.

The Guardian Civic League led by Ms. Bilal objected on grounds that requiring a license for three years would negatively impact Black residents, because they traditionally do not seek to get their children driver’s licenses at 16. In addition, the entry age for cadets was changed from 19 to 25, she said. The concern was that young Blacks that may have an interest in joining the department could potentially lose interest if they have to wait until they were 25.

Black officers were able to convince officials to change the driver’s license requirement and to change the cadet program entry age to 21.

Damon Jones told The Final Call, Black officers are not immune to outrage aimed at White officers over law enforcement-involved shootings that have gone viral in cell phone videos.

“It hurts us tremendously because the community’s going to look at us as traitors to the community, regardless of how we work hard to show that we are in it to protect them,” Mr. Jones said. “But the saddest thing is that our Black leaders, our Black preachers, our Black elected officials are not paying attention to the information that Black law enforcement has brought to them, especially when it comes to legislation and laws.”

Change the language from police brutality to police criminality, and change legislation and laws to hold police accountable for violating policies and procedures, Blacks in law enforcement have urged Black leaders. “They understood the problem. They worked in the problem. And they still failed to change the legislation that adversely affects Black people throughout the United States,” Mr. Jones charged.

Delacy Davis founded Black Cops Against Police Brutality in 1991. It’s among the 25 or more organizations formed to ensure Black cops are included in discussions about policing at every level.

“You know if your father is an abuser or your brother’s an abuser. You know that! How comfortable is that conversation to have in the family? It’s extremely uncomfortable. So it’s even more uncomfortable when you’re having it across racial lines, across ethical lines, across ethnic lines, and the other person’s got a gun and so do you,” Mr. Davis said. “I think that we have to be honest about the conditions that our community is in, and we have to be honest about the solution.”

Part of that solution is for Black officers to tell the truth about what’s happening, what they’ve seen—for some what they’ve done—and for the rest, what they’re willing to do to save their communities, he said.

Stay tuned for coverage from the 2016 National Black Police Association conference for more insight and analysis on the role and duty of Black’s in law enforcement in an upcoming issue of The Final Call.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!