TV News Shooter: 'Just waiting to go boom'

By Starla Muhammad -Assistant Editor- | Last updated: Sep 1, 2015 - 11:12:13 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Black anger and the psychological impact of White supremacy on mental health

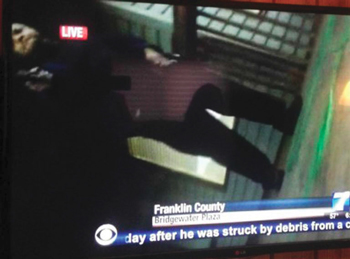

In this framegrab from video made by the camera of WDBJ-TV cameraman Adam Ward, Vester Lee Flanagan II stands over Ward with a gun after fatally shooting him and reporter Alison Parker during a live on-air interview in Moneta, Va., , Aug. 26. Flanagan, who had been an employee at WDBJ and appeared on air as Bryce Williams, posted his own video of the attack on his social media accounts after fleeing the scene. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

|

Authorities said Mr. Flanagan, who went professionally by the name Bryce Williams, was a WDBJ former employee and shot Ms. Parker and Mr. Ward during an early morning live television segment Aug. 26. The shooting wounded Vicki Gardner, executive director of the Smith Fountain Lake Chamber of Commerce.

The victims were White and the alleged gunman was a Black man, who recited his racial grievances over social media and even uploaded a video of the shooting to his Facebook page.

According to the Franklin County Sheriff’s Department, after the incident, Mr. Flanagan fled in a vehicle. Four hours later he was found in the vehicle with a gunshot wound to the head. Authorities said he shot himself after fleeing from a state trooper who attempted to pull him over. Six rounds of ammunition, several stamped letters, a “to do list” and other items were reportedly found in the vehicle.

This undated photo provided by WDBJ-TV, shows Vester Lee Flanagan II, who killed WDBJ reporter Alison Parker and cameraman Adam Ward in Moneta, Va., Aug. 26.

|

A 23-page note authorities said Mr. Flanagan sent to ABC News, received two hours after the shooting, listed a litany of grievances and internal struggles he was battling including financial troubles, “work related bullies” and discrimination due to his sexual orientation and race.

“The church shooting was the tipping point … but my anger has been building steadily ... I’ve been a human powder keg for a while … just waiting to go BOOM!!!!” the letter stated in part. The letter added that he tried to pull himself up from his bootstraps. But, “The damage was already done and when someone gets to this point, there is nothing that can be said or done to change their sadness to happiness. It does not work that way. Meds? Nah. It’s too much,” the letter continued. “And then, after the unthinkable happened in Charleston, THAT WAS IT!!!” “Yeah I’m all f----- up in the head.”

Social media postings attributed to Mr. Flanagan before the shooting reveal the South Carolina massacre of nine Black parishioners at Mother Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by White gunman Dylann Storm Roof was one of his motives. You wanted a race war, bring it, Mr. Flanagan wrote on social media.

“Rage is the perfect cover up for depression. Black males who feel powerless, who feel as though they are not able to bring any level of meaningful purpose to their lives, are often depressed,” noted Dr. Bill Johnson II on BlackMentalHealth Net.com.

Black males are exposed to a large number of social factors thought to increase risk of mental health problems and they have the highest exposure to nearly every social stressor said to increase depression, observed Dr. Johnson II. This depression may be the outcome of unreconciled grief, he continued.

“The primary culprit appears to be the exposure of Blacks to greater inequalities within social and economic environments. This includes an increased exposure to racism and discrimination, violence, and poverty, factors that adversely impact mental health, and may potentially lead to depression,” he wrote in his June article “Black Men and Mental Health: Moving Past Demonization and Denial.” Exposure to discrimination is said to lead directly to mental health struggles in Black males, he added.

Racism in the workplace can destroy your mental health, said Dr. Boyce Watkins of YourBlackWorld.net in a recent video podcast in the aftermath of the Roanoke shootings.

In this framegrab from video posted on Bryce Williams’ Twitter account and Facebook page, Williams, whose real name is Vester Lee Flanagan II, aims a gun over the shoulder of WDBJ-TV cameraman Adam Ward at reporter Alison Parker as she conducts a live on-air interview, Aug. 26. Moments later, Flanagan fatally shot Parker and Ward and injured Vicki Gardner, who was being interviewed. Photos: AP/ Wide World photos

|

“Even though most Black people can’t relate to the idea of going in and killing co-workers, a lot of Black people can relate to the idea of enduring so much discrimination and oppression in the workplace that you are tempted to lash out at somebody, tempted to be violent toward somebody, tempted to go off on somebody,” said Dr. Watkins. “A lot of people have felt that way and I think that should be laid on the table.” People are tired of being marginalized, he added.

If racial inequality, racial discrimination in the workplace are not dealt with a community of marginalized, emotionally boiling people, angry and bitter is being created, he continued.

“Some are getting to the point where they are saying ‘you know what no I’m not going to just let you inflict pain on me,’ ” he said.

Injustice imbalances the mind

Black people have experienced racism from the moment they were captured in Africa and brought to the Western hemisphere and centuries later it has heightened and worsened in the wake of President Barack Obama’s election to office, said Dr. Sandra Cox of the Los Angeles based Coalition of Mental Health Professionals. From slavery onward, generations of Black people in America continue to hope their conditions change. Black people in particular had expectations that came along with President Obama’s election that things would get better, but today Blacks are experiencing racism “every hour on the hour”, Dr. Cox told The Final Call.

“Well, the jig is up because most people now know that with a killing a week almost at one point of a young, Black man or Black girl, that has put us in a different position and we think, hey something’s wrong here,” said Dr. Cox. These incidents and constant negativity work on the psyche, she explained. Dr. Cox went on to say when law enforcement officers are not charged or punished in killings of unarmed Blacks that also has a mental affect.

“How long can you take the put downs, the racism, the denigration, the name calling? How long can you take that before you snap? Fewer and fewer people are able to deal with that and they blanketly say ‘I can’t take it any longer.’” Left untreated or not seeking help could cause a deeper depression or lead to a violent act in order to try and get some alleviation from psychic pain, said Dr. Cox.

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan frequently warns continued injustice and persecution of a people can cause an imbalance in the mind. In his travels around the country in preparation for the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March on October 10 in Washington, D.C. themed Justice Or Else, he has asked the very poignant question “how long can we as a people endure such without responding appropriately when government fails to act?” But he cautioned and warned those who try to twist his words concerning the law of retaliation.

“Every time an act of hatred is done and there is no justice, those who are angered and saddened over the loss of a loved one begins to imbalance the mind and causes them to take drastic action, often resulting in them killing people that don’t even know why they are being killed. Even those practicing the Law of Retaliation are warned not to exceed the limits,” he said during an Aug. 20 address in Memphis, Tenn.

It is not unfathomable or out of the question that Mr. Flanagan experienced workplace discrimination, particularly in a profession with disproportionately fewer Blacks than Whites, and it pushed him over the edge, said Dr. Watkins. Responsibility for this incident doesn’t just lie on Mr. Flanagan, it also lies on the system that creates people like him, he added.

“I really can’t in any way condone the way Vester handled this situation but if we just look at this as a deranged lunatic committed a heinous act, I think you’re going to miss the undertone here,” said Dr. Watkins.

“The undertone is that workplace discrimination makes some people so mad they want to roll up in there and kick somebody’s ass every day. It doesn’t mean they’re going to come in there with a gun, it doesn’t mean they’re going to do it but I know a whole lot of people who go to work and they’re hurting.”

Childhood friends and family described Mr. Flanagan as someone who did not manifest anger issues and was a nice person. His interpersonal conflicts were at odds with the outgoing student some recalled in Oakland, Calif., where he was chosen junior prince at Skyline High School’s homecoming. “He actually was very friendly, always laughing. It seemed like you would always see him kind of joking around,” Lorah Joe, who went to junior prom with Mr. Flanagan in Oakland told an ABC affiliate.

At San Francisco State University, he relished being in the spotlight during group presentations. “He was such a nice guy, just a soft-spoken, well-dressed, good-looking guy. He never had any problems, no fights, nothing like that,” said a high school classmate.

A cousin, Guynell Smith, 69, who had stopped by Mr. Flanagan’s father’s home in Vallejo, Calif., told reporters the family was unaware of any troubles. “He was just a normal kid,” she said. “We knew Vester a different way.”

But to White co-workers in later years, Mr. Flanagan, a reporter who held several jobs at television stations through the years exhibited behaviors described as bizarre, unpredictable, argumentative and confrontational. A college graduate with a degree from San Francisco State University in radio and television broadcasting, Mr. Flanagan seemed well on his way to the flourishing professional career that can be elusive to young, Black men.

And while important conversations about workplace safety and gun control laws have been reignited in light of this latest tragedy, what else must be examined is what happened to Mr. Flanagan along the way.

What drove this bright, educated news reporter to snap?

A downward spiral

Mr. Flanagan who worked at WDBJ less than a year in 2012-2013 was easily offended, said Jeffrey Marks, general manager of the station. A series of problems led to Mr. Flanagan’s ultimate firing when police physically removed him from the premises, he said. Mr. Flanagan filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and also sued the station for wrongful termination alleging racial and sexual discrimination. Both cases were dismissed. He also accused Ms. Parker and Mr. Ward of making racial comments.

Mr. Flanagan filed a grievance with the EEOC and sued a previous employer, WTWC-TV in Tallahassee, Fla. for discrimination and retaliation in 2000 charging among other allegations that he was called a “monkey” by a producer and that a supervisor commented that “Blacks are lazy and do not take advantage of money.”

A July 30, 2012 internal memo from Mr. Dennison to Mr. Flanagan outlined problems in his conduct and behavior and he was subsequently ordered to get help. Mr. Flanagan was ordered to contact Health Advocate, an employee assistance program or risk termination.

Although no underlying or previous diagnosed clinical mental health conditions that may have affected Mr. Flanagan have come to light, the real or perceived racial animus outlined in his correspondence and social media posts were catalysts that helped push—him and other Black men—over the edge.

In 2013 former Los Angeles police officer Christopher Dorner, who was Black, was accused in shootings that left four dead and three wounded. In what authorities called a “manifesto” he declared “unconventional asymmetric warfare” on the LAPD stating he was unfairly targeted and terminated for reporting racism and excessive force by fellow officers.

He recounted experiences in his youth of being called “nigger” by children and adults.

“How dare you swat me for standing up for my rights for demanding that I be treated as an equal human being [?] That day I made a life decision that [I] will not tolerate racial derogatory terms spoken to me. Unfortunately I was swatted multiple times for the same exact reason up until junior high. Terminating me for telling the truth of a Caucasian officer kicking a mentally ill man is disgusting,” the 11-page document read in part.

After fleeing and in a subsequent standoff with police, Mr. Dorner’s remains were found in a burned out cabin near Big Bear Lake, Calif. According to authorities, an autopsy revealed Mr. Dorner died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

In 1994 Colin Ferguson a Black immigrant from Jamaica was convicted of murdering six and wounding 19 people, most of them White on the Long Island railroad train in New York City.

Mr. Ferguson was sentenced to six consecutive 25 years to life in prison.

His original attorneys proposed using the controversial defense of “Black-Rage Insanity Defense” a term coined in the late 1960s that argued environmental hardships caused by racism and White supremacy can psychologically damage Black people to the point of “temporary insanity” and violent, unreasonable acts against Whites.

Mr. Ferguson was well-educated and came from an upper middle class family in Jamaica but after the death of his parents, his family lost its fortune and he moved to the U.S. when he was 23. Only able to secure “menial and low wage” jobs, he became disgruntled with Whites and Blacks he deemed “Uncle Toms.”

When asked about the reality of the mental health aspect of racism and its impact on the Black psyche, renowned psychologist, author and scholar Dr. Nai’m Akbar expressed “curiosity as to why this phenomena is not more common, given our history of oppression and racism.”

According to the FBI of the reported 3,407 single-bias hate crime offenses in 2013 that were racially motivated, 66.4 were motivated by anti-Black or African American bias and 21.4 percent stemmed from anti-White bias. The data did not include the race of the perpetrators of the crimes.

“It would seem that a more ‘normal’ target of our rage and hostility would be directed with acts of violence towards the (White/racist) source of our circumstance than the more frequent tendency to direct it towards other Blacks,” said Dr. Akbar in an email response to questions from The Final Call. “This is only a question without any real concrete data to back up my speculation,” he added.

(Nisa Islam Muhammad and The Associated Press contributed to this report.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!