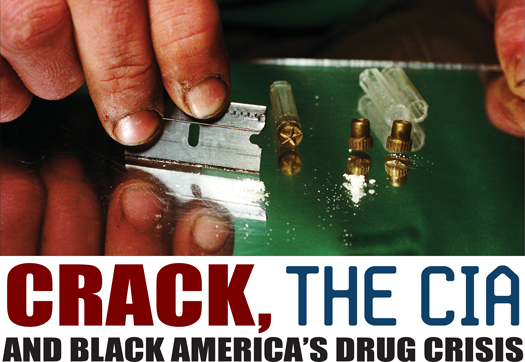

Crack, The CIA And Black America's Drug Crisis

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- | Last updated: Dec 16, 2014 - 8:57:28 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

Kill the Messenger movie rekindles interest and outrage over Central Intelligence Agency ties to drug trafficking and the 1980s crack cocaine epidemic that devastated neighborhoods, destroyed families and put thousands in prison.

Related news:

Crack Cocaine - The Great Conspiracy to Destroy The Black Male (FCN, Min. Farrakhan)

For nearly a decade the CIA, helped spread crack cocaine in Black ghettos (Final Call, 1996)

The death of Gary Webb: The CIA, crack cocaine and the Black community (FCN, 12-31-2004)

One on One with "The Real" Rick Ross (FCN, 12-25-2009)

Reforming the American Gangster: Rick Ross, Frank Lucas (FCN, 03-09-2010)

Contras and Drugs, Three Decades Later (FCN, 10-29-2014)

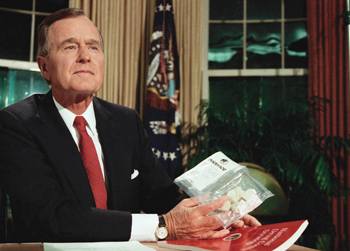

U.S. President George H. Bush holds a bag of crack cocaine as he poses for photographers in the Oval Office of the White House, Sept. 6, 1989 in Washington after delivering his first nationally televised speech. Bush outlined his $7.9 billion plan for the war on drugs.

|

The movie highlights the work, honor and the demise of journalist Gary Webb for his investigation into CIA-connected drug peddling, and the movie release Oct. 10 again raised the important question: How is Black America faring in “post-crack” years?

Not too well, according to activists, political scientists, gang interventionists, and legal experts.

Worse than slavery?

“As far as I’m concerned … looking at the research, looking at what I see in front of me in terms of our community, really, it had a greater impact on certain aspects of our community as Black folks, and in terms of rooting at this fabric of the Black community than enslavement did,” said human rights attorney Nana Gyamfi.

|

“All of us live in these fake little prisons, or many of us do, where we’ve got bars all over our windows. We’re behind gates. We’ve got barred doors. We’ve got all of this that we didn’t have before that, before people started breaking into people’s houses, trying to get whatever they could so they could get some drugs,” Atty. Gyamfi continued.

Broken trust

Another level of broken trust occurred with the idea that people are willing to do almost anything to get drugs once they get addicted, Atty. Gyamfi noted.

More and more in social media and the news, there are reports of mothers who’ve sold their children—some toddlers—for drug money, or they’ve traded children outright for drugs.

It’s something once unheard of in the Black community, observed Elaine Brown, former chairman of the Black Panther Party.

One of the worst things she’s seen about crack is what people will do to get one hit off a crack pipe. “Never in America have we ever had a moment before crack, when our own mothers would turn on their children, would turn out the children and not take care of them,” she said.

“Our mothers, Black women, were always going to take care of everybody’s children. You can look in the Black house. When everything else fails, somebody’s grandmother or mother will take care of somebody’s children … There was always a big mama,” she said.

In this Oct. 10, 2006 file photo, a Los Angeles police officer counts the number of doses of crack cocaine, as he files an evidence police report after a drug related arrest in the Skid Row area of downtown Los Angeles. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

“When we started having women to put their own children out for prostitution to get crack, well, I knew it was all over,” Ms. Brown said. “And then, on top of that, they used that as an excuse to lock us all up.”

The long-time activist views “Kill the Messenger” as an important film for Black people to see. “It’s a good story of a man who (Gary Webb) wasn’t a hero. It wasn’t like he went out to help Black people, but he started out doing research. He realized what he had found and he fearlessly started publishing it … He showed these people made a deal with the devil and dumped this cocaine into our communities,” she said.

|

The Black family buckled under crack in many ways, the legal activist further noted. People were embarrassed by crack addicted family members so communication stopped. People didn’t know what was going on with their families and were afraid to ask, Atty. Gyamfi added.

“It really has a physiological, an emotional, mental, and certainly a spiritual effect on our people, and I don’t think anything else has come close,” she continued.

Kelvin Scott holds up a plastic bag holding fl our, representing cocaine, as he joins marchers protesting alleged CIA involvement in the crack cocaine trade Feb. 22, 1997. Several hundred demonstrators marched in protest at the Los Angeles Federal Building and held a rally on the South Lawn of City Hall. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

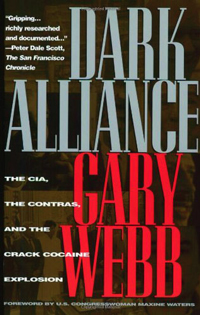

‘Johnny Appleseed of crack’

Gary Webb was a reporter for the San Jose Mercury News when he wrote a groundbreaking series called “Dark Alliance.” The series, published in 1996, was based on a yearlong investigation. It essentially exposed connections between the CIA and millions of dollars in cocaine sales that benefitted Nicaraguan Contras in their 1980s fight against the ruling leftist Sandinista government. Congress had quashed funding for the anti-Communist fighters loved by Ronald Reagan and the right wing. Covert support for the group led to the 1986 Iran Contra scandal.

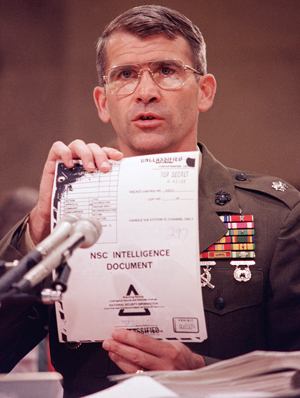

Lt. Col. Oliver North holds up a National Security Council Intelligence Document marked “TOP SECRET” during testimony before the House-Senate investigating committee at the Iran-Contra hearings in Washington July 11, 1987. The Contra guerillas were also involved in drug trafficking to raise funds.

|

But on the other side of the equation, CIA operatives tied to the Contras opened the floodgates for cheap cocaine through drug-selling in the Black community in Los Angeles, which helped fuel a shift from high priced powder cocaine to a cheap rock-like, cooked version that became widely known as crack, the San Jose Mercury News reported. The series showed connections between a CIA operative, the drug selling Fuerza Democratica Nicaraguense, the largest of several Contra groups, and drug dealer Ricky Ross. The drug money was used by the FDN to buy weapons and war material.

The series also focused on the devastating impact crack cocaine had on the Black community in Los Angeles and the shocking numbers of Blacks prosecuted for some connection to the drug.

It was received with great interest, but then attacked by major media outlets and the Central Intelligence Agency. The Mercury News retracted the series. Reporter Webb stuck by his work but couldn’t get a job. He was reported dead from suicide in 2004.

“As many of Webb’s defenders have noted, if journalists had put half the passion into following up the implications of that report that they put to discrediting Webb, we’d know a lot more about the darkest side of America’s national security state,” observed Greg Grandin, who wrote a piece for The Nation published online as “The New York Times’ Wants Gary Webb to Stay Dead” in October. The Los Angeles Times, the New York Times and the Washington Post were among those who aimed high level-scrutiny at the Dark Alliance series. As Mr. Grandin notes, “the Los Angeles Times alone assigned seventeen reporters to leverage the inherent mysteries of the national security state to cast doubt on Webb.”

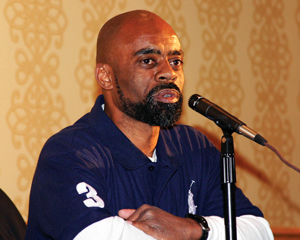

“Freeway” Ricky Ross, former drug dealer now inspirational and motivational speaker. He now warns youth about the dangers of drugs and that lifestyle. Photo: Tim 6X

|

“Freeway” Ricky Ross was convicted of drug trafficking and sentenced to life in prison. His sentence was later reduced to 20 years, with further reductions as a model inmate. He was released from prison in 2009.

He regrets being used a pawn in the CIA-linked operation that spread drugs and despair in the Black community.

|

Mr. Ross said the crack epidemic also created a different, dangerous mindset: “It created a mindset that we should attack life as easy as we can and try to get shortcuts.”

One of the biggest negative residuals of the crack cocaine epidemic is wasteful spending, Mr. Ross told The Final Call.

“We don’t really respect money anymore. We take our money and we spend it on things that are really fruitless, that don’t have any real value to it, and all that comes from making fast money and making it too easy,” he said.

The author and motivational speaker, who was once a celebrated multi-millionaire cocaine kingpin, said he’s learning there’s a big misconception of what he and others did when they started selling drugs.

The youth admire his old antics and many rap about drugs and guns, but the purpose and idea behind those past dealings was people trying to get a head start, Mr. Ross said.

“But what it’s become, the mindset, is that you can take this and make yourself look bigger and feel bigger than everybody else,” he said. Ricky Ross lost a court battle to keep a popular, rapping ex-corrections officer from using his name.

‘Never questioned the system’

Alfredo Boza, spokesman for a multi-agency task force, shows a tableful of kilos of cocaine and weapons seized, April 16, 1998, in Westchester, Fla., southwest of Miami. One arrest was made and almost $2 million were seized when police found an alleged cocaine to crack cocaine processing lab. Photo: AP/Wide World photos

|

“It was meant to be that way. We never questioned the system. We just automatically assumed that everything is correct, that it’s operating exactly how it’s supposed to be,” Mr. Sherrills stated.

But while some were enjoying what they considered a benefit and a quick way to get money, many didn’t know the larger impact it was having, he said.

At the same time the government operatives helped bring crack in, activists argue, factories closed, jobs vanished, and in the process, gangs became surrogate families. Then they became violent social groups.

Mr. Sherrill’s seen a lot of bloodshed and young, Black males ushered into prison as a result of the crack epidemic, including two of his own brothers, who are serving life sentences. “Not even for having drugs, but conspiracy. Nobody even died. The sentencing is ridiculous,” he said.

“When you look at 20 years later from the crack cocaine trade to now, I think we’re worse off now than we were then,” Mr. Sherrils said.

Sentencing disparities

“That whole piece was essentially used to build the Prison Industrial Complex and to essentially sweep Black men off the streets, possessing five rocks in their pocket when you’d catch a White boy with a pound of powder cocaine in his trunk and he would get probation,” said Dr. Anthony Asadullah Samad, author, columnist and professor, of the crack cocaine crisis.

The difference in sentencing for crack cocaine was 100 to 1 for powder cocaine. Powder cocaine was associated more with White defendants. In 2010 Congress passed legislation that reduced sentencing to 18 to 1. While the disparity still exists, the reduction meant some 12,000 offenders became eligible to seek reduced sentences.

Human rights activists, civil liberties groups and politicians argued the change made a difference in some people’s lives, but there is still more to do.

In California, the Drug Policy Alliance, NAACP, ACLU and other criminal justice reform groups are supporting proposed legislation to eliminate disparities between crack and cocaine sentencing.

In March, state Senator Holly Mitchell (D-L.A.) introduced Senate Bill 1010 to equalize the penalties.

“Same crime, same punishment is a basic principle of law in our democratic society,” said Senator Mitchell, chair of the Black Caucus and member of the Senate Public Safety Committee.

“Yet more Black and Brown people serve longer sentences for trying to sell cocaine because the law unfairly punishes cheap drug traffic more severely than the white-collar version. Well, fair needs to be fair,” she continued.

According to intake data from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Senator Mitchell’s office reported people of color account for over 98 percent of persons sent to California prisons for possession of crack cocaine for sale.

From 2005 to 2010, Blacks accounted for more than 77 percent of state prison sentences for crack possession for sale, Latinos accounted for 18 percent, and Whites, less than two percent. The document further noted Blacks make up nearly seven percent of the state’s population, Latinos 38 percent and Whites 39 percent.

Dr. Samad is certain the full impact of crack on the Black community will be shown in time, largely because there’s a limit on on the length of time governments can keep documents secret.

“People will eventually find out, just like we are now witnessing within the last 15 years, the depth of their infiltration in the Nation (of Islam) and the civil rights movement,” he said.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!