Racism, repression and resistance

By Richard B. Muhammad | Last updated: Oct 14, 2014 - 9:16:06 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

Protesters stand in front of police outside the Ferguson police station, Oct. 11 in Ferguson, Mo. Organizers of the four-day Ferguson October summit are protesting the shooting of unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

The passion, emerging power of Black youth fuel demands for justice

ST. LOUIS, Mo. (FinalCall.com) - A moment borne out of angry Black youth facing heavily armed police officers, snarling police dogs, tear gas, rubber bullets, pepper spray and armored military personnel carriers in the streets continues to grow into a movement.

Philosopher Dr. Cornel West, left, and another man are taken into custody after performing an act of civil disobedience at the Ferguson, Mo., police station Oct. 13, as hundreds continue to protest the fatal shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown by police in August. In fact, tensions escalated last week when a white police officer shot and killed 18-year-old Vonderrit Myers Jr., who authorities say shot at police before he was killed.

|

“Missouri is the new Mississippi,” said Tef Poe, a young activist and hip hop artist from St. Louis.

Conditions and protests over two months in the streets of “New Mississippi” mushroomed into a weekend of civil disobedience, protests, marches rallies, prayers, hip hop performances and rebellion. The Weekend of Resistance, Oct 10-13, “#FergusonOctober,” drew young people, activists, organizers and elders from across the country.

Their presence flowed from Ferguson, Mo., a predominantly Black suburb, where Michael Brown was shot down by a White police officer in early August to St. Louis, which had a police shooting just before the gathering.

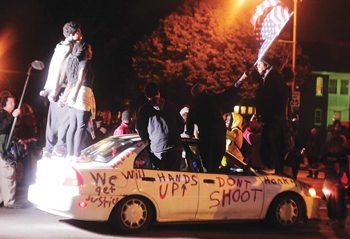

Youth protestors have taken to the streets to protest and demonstrate their anger and frustration with the shooting deaths of two young, Black men in Ferguson and St. Louis, Mo.

|

When social media beamed videotaped images around the country and the world—Black resistance had begun.

‘No justice, no peace; no racist police’

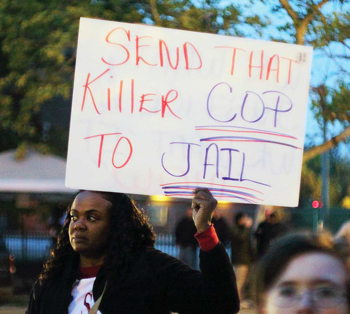

Protestors question why no arrest has been made of the police officers who shot Mike Brown in Ferguson and Vonderrit Myers Jr. in St. Louis.

|

While “Turn Up Don’t Turn Down, We Do This For Mike Brown!” was an initial battle cry, by Monday, Oct. 13, “Justice for Vonderrit!” was added to the cry. The 18-year-old Black male was killed by an off-duty officer in St. Louis who was moonlighting as a security officer in the city’s Shaw neighborhood. Police chief Sam Dotson told the media the youth was killed after firing a weapon at the still unnamed officer. The shooting victim’s family denies the young man was armed. All he had was a sandwich after exiting a shop in the multi-racial neighborhood when the officer aggressively approached him and friends, they said.

Protestors gathered in the Shaw neighborhood to call for justice for Vonderrit Myers, Jr., and Michael Brown, Jr. They stopped traffic and sat-in at a convenience store. Police responded in a militarized fashion to peaceful demonstrations and civil disobedience, activists said.

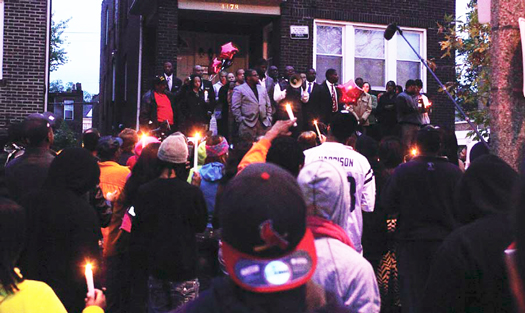

A candlelight vigil was held for Vonderrit Myers Jr. who was shot to death by a White police officer in St. Louis who was moonlighting as a private security officer. Photo: D.L. Phillips

|

Protestors took to streets for Moral Monday and engaged in civil disobedience outside Wal-Mart and other targets in St. Louis and massed Oct. 13 outside the Ferguson Police Dept. Dr. Cornel West, who spoke at a program the previous night and participated in a 2 a.m. sit-in at St. Louis University, was among those arrested.

“I didn’t come here to speak, I came to get arrested,” he had said at the Chaifetz Arena on the campus of St. Louis University. His word was made bond the next day as police took him away in handcuffs.

Black youth expressed their outrage over police killings during recent weekend of resistance.

|

The crowd chanted its agreement and young people took to the stage. On stage, Tef Poe offered his street level assessment of issues and problems.

So-called gang members like the GD’s and the Vice Lords are not on this stage, he noted. But it wasn’t the professional people or academics out on the streets protecting us, it was the brothers with tattoos and their shirts off, he declared.

We are not professional activists or organizers but we are real people dealing with real problems, he said.

“I don’t need Don Lemon to tell me what happened. I was there,” said Tef Poe, referring to the CNN newsman.

Elders were challenged to listen to, respect and support this emerging crop of fearless young leaders, who have not stopped their demands for justice.

When a White man shouted from the audience about contributions Whites had made to Blacks, the mixed race crowd started to boo. “Get your people! White folk get your people, collect him,” shouted a Black woman standing near steps inside the arena.

Activists Tef Poe and Ashley Yates emcee national rally against police violence.

|

A midnight march for justice

“I thank everybody for coming out. My son was loved and he still is loved,” said Vonderrit Myers, Sr., in the early morning hours of Oct. 13, with his wife Syreeta by his side and surrounded by family members and a huge crowd that marched about 40 minutes to the university campus. The trek included a standoff with police armed in riot gear, holding and beating shields with batons. After some negotiations and insistence that protestors had the right to march on sidewalks and talks with legal observers, police pulled back and the group was allowed to proceed.

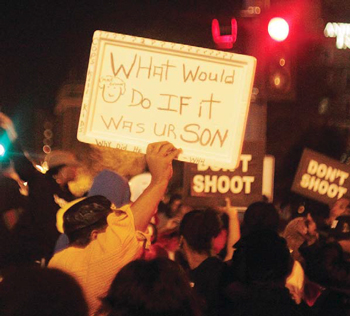

Thousands came to St. Louis and Ferguson, Mo. to participate in a demonstration against police violence, racism and oppression.

|

“We are here to destroy systemic racism and White supremacy,” said one of the protest organizers as the crowd applauded and cheered. That isn’t anti-White, it is anti the 99 percent who exploit the masses of the people, he added.

“I refuse to have my children grow up in this world,” he said.

Hardship forging new leadership

The boldness of Black youth was on display throughout the weekend as was the political and organizational growth of young people who two months earlier were living normal lives.

Joshua Williams, 18, is one of the emerging young leaders and lives in Ferguson. According to the young activist, Michael Brown was a first cousin.

Keep in mind that Mike Brown died for an unjustified reason, he said. “That could have been your son laying in the street,” said Joshua. “Hands up means I surrender, don’t shoot me down in the streets.”

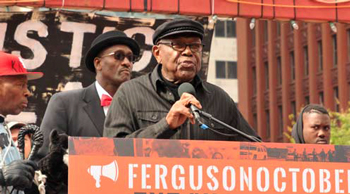

A. Akbar Muhammad of the Nation of Islam speaks during major protest rally in St. Louis. Photos: Cartan X. Moseley

|

Calvin Green stood outside the Ferguson Police Station as hip hop music played and police lined up in riot gear. A thin yellow tape separated Mr. Green from the armed officers. He came in with a group of students from Kalamazoo, Mich., that included students from Western Michigan University and activists.

“God allowed me to be here for a reason,” he said. “God allows us to be here for a reason. In our path we are supposed to serve our people, confronting his evil,” he said.

“Our main weapon is love which is what I am showing to people in Ferguson,” Mr. Green added.

Expressions of love and support came from stages, through megaphones and through one on one conversations and group discussions.

Some 800 people turned out Oct. 10 for a Capital Justice Now March and Rally at the Buz Westfall Justice Center in Clayton, Mo. Rain did not deter demonstrators who want County Prosecutor Bob McCullouch to resign the case involving the death of Michael Brown. Black leaders, youth and politicians have called for a special prosecutor in the case. Photos: Cartan X. Moseley

|

Parents are too busy, schools punish them and police and adults want them to go away, she said. But, added the Caucasian pastor, it’s time to stand with them. “The whole damn system is no damn good,” said Rev. Lamkin, echoing a chant youth have shouted day and night.

Tory Russell of Hands Up United marveled at how far things had come in a little over 60 days. Speaking after the major Saturday rally that drew thousands to downtown St. Louis, he described himself Oct. 11 as a conscious person before Mike Brown’s death. But he and the young people are maturing in activism. They remain strong but more disciplined, more focused, and perhaps more committed.

Mr. Russell, in his twenties, is an organizer and part of a movement that has international reach. People have to go home and work, organize against police violence and injustice where they live, he said. This young movement has veteran activists talking about poverty, racism, voracious capitalism and universal rights—but it started with young people making a single declaration: “Black lives matter!”

Their work remains undone, justice has not come. There has been no indictment for the shooting of Mike Brown and the shooting of Vonderrit Myers, Jr. has been written off as justified by some.

But this movement didn’t start with approval from the police and the powerful and youth leaders say disruptions will continue. We won’t go back to business as usual, things will never be as they once were, they vow.

They have not left the streets—and there is no sign that they will.

But this movement didn’t start with approval from the police and the powerful and youth leaders say disruptions will continue. We won’t go back to business as usual, things will never be as they once were, they vow. They have not left the streets—and there is no sign that they will. They want justice.

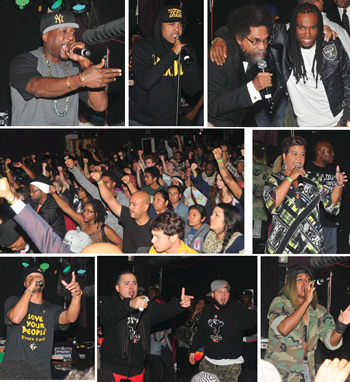

Hip hop artists Talib Kweli, Dead Prez, Jasiri X, Rebel Diaz and others joined activist Rosa Clemente, intellectual Cornel West and others for a five hour hip hop and resistance event on Oct. 12 in St. Louis. The concert was part of the Weekend of Resistance organized to bring attention to the problem of police brutality, police murder, police oppression and to support the efforts of young leaders seeking justice for Michael Brown, an unarmed Black youth shot to death by a White Ferguson, Mo. police officer in August. Photos: Cartan X. Moseley

|

They are unafraid of police and have little patience with those seen as apologists for injustices they face and the murder of their brothers and sisters. When mocked outside a Cardinals baseball game, young demonstrators chanted: “Who do you want Darren Wilson? How do you want him? Dead!”

Youth who are not necessarily part of the organizations want justice too. When police shootings have happened in St. Louis, their cry has been, “Hands Up! Shoot back!”

If justice is not done, nothing may be able to contain the explosion, and law enforcement agencies are already planning for potential riots.

“Missouri authorities are drawing up contingency plans and seeking intelligence from U.S. police departments on out-of-state agitators, fearing that fresh riots could erupt if a grand jury does not indict a white officer for killing a black teen,” Reuters reported before the Weekend of Resistance.

Meetings are held two to three times a week with FBI involvement and Missouri law enforcement officials have been in contact with police chiefs in Los Angeles, New York, Florida and Cincinnati, Ohio and other jurisdictions as they prepare for the grand jury decision, according to the report.

“If charges are not brought against Wilson, police fear an outbreak of violence not just in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, but across the greater metropolitan area and even in other U.S. cities, according to St. Louis County Police Chief Jon Belmar and others involved in the planning meetings,” said Reuters.

“Brown’s killing sparked days of protests in Ferguson in August and looting that caused millions of dollars of property damage. Police were sharply criticized for what was seen as a heavy handed response to the protests, firing tear gas and arresting hundreds of people,” Reuters said.

The grand jury empanelled by county prosecutor has until January to decide if charges against officer Wilson are warranted.

“Adam Weinstein, co-owner of County Guns, said sales were up 50 percent since Brown’s shooting, mostly among white residents fearful of riots who are buying Glock, Springfield and Smith & Wesson handguns, and shotguns. ‘They are afraid the city is going to explode,’ Weinstein said,” according to Reuters.

During a session with lawyers Blacks also expressed anger. “ ‘We are tired of dead bodies in our community,’ Mauricelm-Lei Millere, an advisor to the New Black Panthers, shouted at the audience. ‘We are not going to take it anymore,’ ” Reuters reported.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!