Libya proof UN is tool for West's takeover of Africa

By Saeed Shabazz -Staff Writer- | Last updated: Oct 28, 2011 - 1:38:27 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

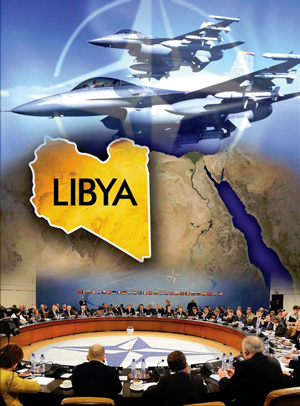

The resolution initially established a NATO-operated “no-fly zone” in Libya and included the subsequent targeting of Libya's leader for the past 42 years, Col. Muammar Gadhafi, Oct. 20 after his convoy in Sirte was struck by NATO air defenses.

'The UN in Africa represents the new colonialist grab for Africa's resources, that has nothing to do with human rights.' — Sara Flounders, Co-founder, The International Action Committee |

“We are very concerned about the role of the UN in Africa,” admitted Ambassador Baso Sangqu of South Africa.

“Yes, we are concerned about the UN's handling of African issues,” Ambassador Atoki Ileka of the Democratic Republic of the Congo said.

On Sept. 22, during his speech before the UN General Assembly, Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe said it was “sad” that the International Criminal Court and the UN Security Council were being used by “powerful countries” to target leaders from the developing world, in particular African leaders.

The UN was used to sanction his regime after the international community raised questions concerning the 2006 presidential elections in his nation, President Mugabe noted. But, he argued, the problem wasn't politics or voting. “When we in Zimbabwe sought to redress the ills of colonialism and racism, by fully acquiring our natural resources, mainly our land and minerals, we were and still are subjected to unparalleled vilification and pernicious economic sanctions,” he charged.

Some say UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon's role in letting the UN Dept. of Peacekeeping Operations, under Frenchman Alain LeRoy operate with the French Force Licorne to remove Cote d'Ivoire's former president from power still raises questions.

French jets and UN peacekeeping helicopters fired on the compound where Laurent Gbagbo and his family had taken refuge following accusations of election fraud and violence.

“The contention over Africa has become intense over the last decade,” said Prof. Mahmood Mamdani, an African expert at Columbia Univ. in New York City. The professor made an appearance on the Pacifica Radio “Democracy Now!” on Sept. 14 and discussed what was taking place in Libya.

“The implications of NATO's intervention in Libya, threatens to increase the militarization of the African continent,” he warned. In October, President Obama announced U.S. military advisors were going into Uganda, Kenya and Somalia. The assignment for East Africa was supposed to bring to justice the leader of the rebel Lord's Resistance Army, which has wrecked carnage in the area, the president said.

“The role of the UN in Africa has been problematic since its inception,” said Bill Fletcher Jr., writer, commentator, author and an expert on Africa and the Caribbean. He referred to the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo as an example of what the UN history has been on the continent.

“Clearly the UN has been used as an instrument to advance imperialist foreign policies,” said Mr. Fletcher, who is also the former head of the U.S.-based TransAfrica lobbying group.

Emira Woods, a policy analyst at the Washington-based Institute for Policy Studies, told The Final Call it was “really clear that the UN is using the policy of ‘Responsibility to Protect' civilians as a fig leaf for regime change in African nations.”

“The UN in Africa represents the new colonialist grab for Africa's resources, that has nothing to do with human rights,” declared Sara Flounders, co-founder of the International Action Committee. We are calling for NATO and the U.S. to leave Africa, she said.

Attorney Roger Wareham, a member of the Brooklyn-based December 12th Movement, told The Final Call he agreed with the view that the UN is very bad for Africa and African leaders.

“The West is using the UN to justify its efforts to re-colonize Africa, so that they may lay hands on its resources,” he said. Mr. Wareham said his organization remains concerned that there will be an attempt to remove President Mugabe from office in the near future.

“President Mugabe stands for the same things that President Gadhafi espoused, a United States of Africa, and the control of the continent's resources by African people,” Mr. Wareham said.

Other analysts say the defacto conquest of Libya by the U.S., through its imperial partners at the UN, heralds a modern version of the “scramble for Africa” at the end of the 19th century.

In the meantime, the UN continues to work in Libya, out of sight of most of the world. In September, the UN Dept. of Peacekeeping Operations sent staff to Tripoli, the Libyan capital, under a unanimous UN Security Council resolution that mandated steps to initiate economic recovery, to restore public security, plan for elections and to ensure transitional justice.

The council's resolution establishing the mission called for a modification of the assets freeze, as called for under Resolution 1970. The assets of the Libyan National Oil Corp., Libya's Zueitina Oil Co., and Central Bank of Libya, Libyan Arab Foreign Bank, Libyan Investment Authority and Libyan Africa Investment Portfolio were freed under the new resolution.

According to Devex, an international business development service, the UN approved the release of $1.5 billion held by the United Kingdom, $1.5 billion in frozen Libyan assets in U.S. banks, $2.14 billion in French banks, $3.52 billion in Italian banks and $2.2 billion in Canadian banks.

On Oct. 21, the Office of the High Commissioner on UN Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland called for a probe into Col. Gadhafi's death. “We believe there is a need for an investigation and more details are needed to ascertain whether he was killed in the fighting or after his capture,” an OHCHR spokesperson said.

The Security Council held a meeting on Libya the evening of Oct. 21. The Russian delegation proposed a draft resolution to end NATO's no-fly zone mandate. Ian Martin, the UN special envoy for Libya, told reporters during a video tele-conference that the NATO mandate won't end in the foreseeable future.

Secretary-General Ban issued a statement Oct. 20, calling on “all sides in Libya to lay down their arms and work together peacefully to rebuild the North African nation.” But his next line raised the ire of African ambassadors Ileka and Sangqu. “Clearly, this day marks an historic transition for Libya,” Secretary General Ban said. “Not correct, what Secretary-General Ban said, historic for whom?” asked Ambassador Ileka. “The secretary-general's remarks, saying an ‘historic transition' are not diplomatic,” Ambassador Sangqu added.

Assassination of Libya's revolutionary leader condemned (FCN, 10-25-2011)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!