Protestors condemn Ghana-U.S. military deal

By Brian E. Muhammad -Staff Writer- | Last updated: Apr 16, 2018 - 1:19:36 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

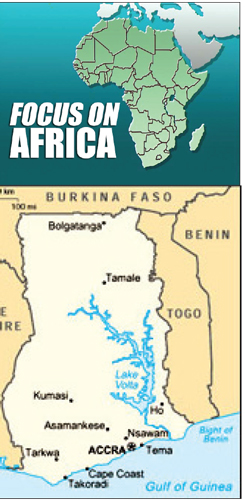

Demonstrators filled the streets of Accra, Ghana, protesting a decision by Parliament that ratified a Defense Cooperation Agreement with the United States.

There were serious questions about what the pact meant for the West African nation. Some see a sign of American military expansion in Africa. Others see serious threats to Ghana’s national sovereignty and security.

“First of all … it undermines the independence and territorial integrity of Ghana,” said Kwesi Pratt, managing editor of Ghana’s Insight newspaper.

Talking to The Final Call from Accra, Mr. Pratt pointed to Ghana’s importance as the nation that led the African struggle against colonialism south of the Sahara. Ghana celebrated its 60th anniversary of independence from British colonialism March 6.

The journalist also noted that the history of American involvement in Africa “is not an enviable” one. In the 1960s, the Central Intelligence Agency orchestrated the 1966 coup against Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president after independence from Britain. In 1961, the U.S. was complicit in the capture, torture and murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of a free and independent Congo, he added.

|

Ghana is lauded as an example of democracy working in Africa with relatively smooth elections and transfers of power. Although the decision went through the democratic process, it has become a source of major upset for Ghanaians. Disappointment with the administration of President Nana Akuffo-Addo for making the deal has been expressed. Protesters marched with placards that read, “Trump take your base elsewhere,” “Ghana not for sale,’’ and “Incompetent government, incompetent agreement.” Opponents scoffed March 23 at monetary aid of $20 million that came with the deal—money the U.S. government says is for training and equipping the Ghanaian armed forces. Critics argue the amount is an insult from President Trump who called African nations “shithole” countries. Some compared the “small” allocation to President Trump’s proposed $33 billion, 900-mile long and 30-foot high U.S.-Mexican border wall.

“It’s unprecedented,” said Mr. Pratt. “The United States soldiers will have diplomatic immunity, and they can enter into Ghana without a valid passport and visa and they cannot be searched by Ghanaian security authorities.”

Mr. Pratt also raised concerns about whether U.S. military weaponry will flow into Ghana unchecked, including possible “biological and chemical” weapons.

“These are very serious implications—not just for Ghana—but the whole of West Africa,” said Mr. Pratt.

On the international stage, the agreement is bad for Ghana’s credibility, he argued. “Our position as a Non-Aligned country has been deeply compromised,” Mr. Pratt said. “By signing this agreement, we can no longer claim to be Non-Aligned in international relations.”

The U.S. government dismissed fears the agreement threatens Ghana sovereignty as baseless and maintains the pact doesn’t give the U.S. military rights to enter Ghana without government permission.

Both the government of Ghana and U.S. Ambassador to Ghana Robert Jackson, in a statement, denied the pact leads to establishment of a military base.

“The United States has not requested, nor does it intend to request, the establishment of a military base in Ghana or the permanent presence of U.S. troops in Ghana,” the statement said. Amb. Jackson said reports alleging otherwise are “inaccurate and misleading.”

U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Andrew Notbohm, a military policeman with Bravo Company, 4th Law Enforcement Battalion, tightens a riot control helmet of a Ghana Armed Forces soldier during nonlethal training for the Ghana Armed Forces' 2nd Engineer Battalion at the 48th Engineer Regiment Wajir Barracks in Accra, Ghana, June 20, 2013, during Western Accord 2013. Photo: U.S. Army/Master Sgt. Montigo White

|

“So, Ghana now brings America in, and I’m sure the excuse is nearby Nigeria is suffering with Boko Haram, and they want to protect Ghana from Boko Haram,” said Abdul Akbar Muhammad, international representative of the Nation of Islam. “They started this process and it was as though they were trying to keep their real motivation a secret. All these moves that America is making is to get its foot planted across Africa as a counterweight to China.

“It all started with AFRICOM … and the world realizes that the resources in Africa are important because China is in Africa getting those resources to turn the wheels of industry in China and America feels it’s losing out,” Mr. Muhammad said. “This is why we have this problem.”

Mr. Muhammad has dual citizenship in Ghana and the U.S. and recalled leaders like President Nkrumah and later Muammar Gadhafi of Libya “warned all of the African nations against allowing foreign entities to set up military bases on the continent.”

Samia Nkrumah, former Member of Parliament and daughter of former President Nkrumah, said the military pact must continue to be rejected and echoed her father’s call for African unification to combat America’s moves on the continent.

“Kwame Nkrumah tells us in Africa Must Unite, 1963, that ‘if we do not unite and combine our military resources for common defense, our individual [African] States, out of a sense of insecurity, may be drawn into making defense pacts with foreign powers which may endanger the security of us all,’ ” Ms. Nkrumah said in a March 20 Facebook post.

The United States has a considerable number of Defense Cooperation Agreements with countries around the world, “including European, Asian and African partners,” countered Amb. Jackson in his statement.

The U.S. embassy said the agreement is only a legal framework to govern its ongoing security cooperation with Ghana.

“The security cooperation spans more than 20 years and has included numerous bilateral and multilateral training activities in Ghana,” said the U.S. Embassy in Ghana website.

Both militaries have cooperated in numerous joint training exercises. There is a bilateral International Military Education and Training program, a Foreign Military Financing program and humanitarian affairs projects, said AFRICOM’s website.

Ghana ex-president Jerry-John Rawlings called the decision the wrong move for the country he led three times between 1979 and 2001. “Ghanaians may love Americans, but not to the extent of living with foreign troops on such a scale,” said the former president. “Ghanaians have enough foreigners dominating their economic and social life. Adding foreign troops to the discomfort would be a bit too much.”

President Akuffo-Addo’s predecessor, John Dramani Mahama, expressed support for the protesting Ghana First Patriotic Front and other voices of opposition.

“I join in declaring #GhanaFirst as my compatriots and other democratic forces converge to demonstrate their opposition to the Ghana/U.S. military agreement,” former President Mahama said in a March 28 tweet.

Protesters said demonstrations will not stop until the government amends the agreement. Ghana and the U.S. are longtime allies, but critics feel America is being given too much for so little. The agreement gives the U.S. military access to Ghana’s radio spectrum, with authority to build a communications network, airport runways and facilities.

“National sovereignty is not up for sale; I mean there’s no price which can compensate for national sovereignty,” Mr. Pratt said.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!