Art and activism in the African liberation struggle

By Jehron Muhammad | Last updated: Nov 13, 2019 - 10:33:49 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

It is a “form of protest that speaks to the youth of today; it’s a form of protest that speaks to me and you and every single one of us,” he argues.

Keith Mundangepfupfu

|

In the April edition of Carnegie.org, in a piece titled “Visual Activism in Africa: The New Storytellers,” Aruna D’Souza wrote, “Africa is a continent of 54 nation states, more than 1,500 languages, and roughly 3,000 ethnic groups, making it the most diverse and culturally rich place on earth. It is impossible to speak of it as a singularity. This is why many scholars on the continent refer not to African art, but to the arts of Africa when speaking of the visual and material cultures produced across a vast range of eras, spaces, and traditions.”

One of many artists to choose from is South African Nomusa Makhubu, who uses colonial photographs to help highlight the deep history of South Africa’s ethnic divisions. She high-lights how museums have historically been organized and explains how complex social-political identities have been framed in static ways.

By projecting historical images over her body, this artist is giving commentary on how living subjects are informed by and can resist colonial modes of representation and classification.

Nomusa Makhuba, A South African artist and researcher uses colonial photographs to highlight the deep history of South Africa’s ethnic divisions

|

“Even though it is my body depicted in these works, rather than being explorations of the self, the project explores the representation of African women,” she says. “Colonial photography is the documentation of violation and the terror of dispossession. Reenacting these scenes brought me closer to this terror. For me, the past is living memory—this work is a way of coming to terms with the persistence of the same repressive structures.”

Activist art in the 2018-19 Sudan uprising helped make the world acknowledge the struggle isn’t just about reduction of a subsidy, or a price of “bread protest,” but a battle for freedom, justice and equality.

“The Bread Loaf,” a clever adaptation of Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam,” in which Adam holds a loaf of bread as he reaches for God, was superimposed on an iconic Sudanese backdrop of a crowded bus depot. “From the growing poverty and homelessness to the worsening public transportation issues, Abdul Rahman Alnazeer’s tableau succinctly and powerfully displays many of the issues faced by citizens in Khartoum during that period,” noted Okayafrica.com.

Patrice Lumumba featured on the poster Day of Solidarity with the Congo, 1972

|

Enslaved Africans and their descendants helped create Cuba’s unique and vibrant culture, most evident in its music, dance and art. Today, a significant proportion of Cubans can trace their ancestral roots to Africa.

In a recent BBC piece, “How Cuban art fed Africa’s liberation struggles,” an exhibition of Cuba-produced posters and magazines are displayed. The exhibition highlights support Commandant Fidel Castro and the Cuban people gave to 1960s African liberation movements.

The artwork was produced by the Organization of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America, founded in 1966 during a Tricontinental Conference in Havana. The stated conference goal was to “combat U.S. imperialism.”

The iconic photo of Che Guevara depicted in a poster is one of the most recognizable examples of revolutionary art. Guevara went to what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1965 on a failed mission to foment revolt against a pro-Western regime four years after the assassination of Congolese independence hero Patrice Lumumba.

Another poster image is of President Lumumba, whose head takes the shape of Africa.

“The portraits are particularly interesting because they have all these pop art influences that you might not expect to see, so they are kind of celebrating people but in a genuinely celebratory way—rather than having a sort of like lumpen socialist-realist aesthetic,” says Olivia Ahmad, curator of the exhibition at the House of Illustration.

By early 1964 the Hon. Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam were publishing “Muhammad Speaks” newspaper, which one writer declared “had surpassed Marcus Garvey’s defunct ‘Negro World’ as the most important publication ever produced in the West by people of African descent.”

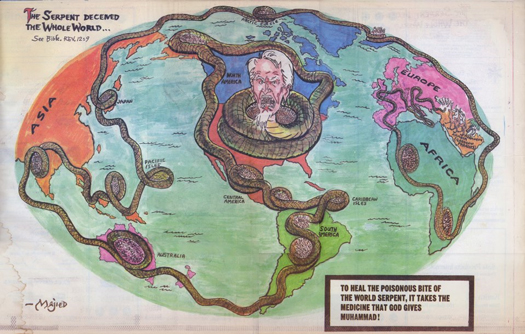

Eugene Majied iconic drawing of the serpent that deceived the whole world appeared as a center fold in Muhammad Speaks. The illustration appeared as a serpent with the head of Uncle Sam, with a body wrapped around every continent on earth.

|

Not only were African leaders, including Kwame Nkrumah and Achmad Sukarno of Indonesia frequent guest columnists, it was also the premier weekly for news pertaining to global liberation struggles. And, the artwork of Eugene Majied, and cartoons by Majied and Gerald 2X gave much substance, the world over, to the axiom, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

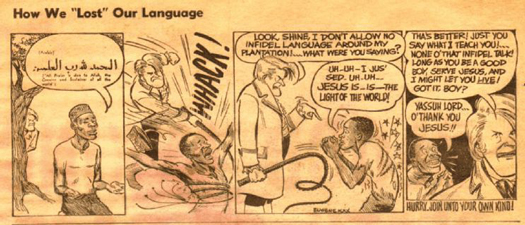

A case in point is a four-panel comic by Majied, “How We Lost Our Language” in the December 1961 edition of Muhammad Speaks. The cartoon introduced then boxer Cassius Clay, later named Muhammad Ali, to concepts of self-knowledge and struggle. By inspiring Ali, it helped change the wider culture and helped shape the future of sports. Ali became a global figure who championed Black rights in Africa and America.

Years after the encounter, Ali would remember nearly every detail of the cartoon. In a letter Ali described the story: In the first panel, a plantation overlord comes across an enslaved man, dressed as a Muslim, who is saying a prayer that is written in Arabic script. The overlord whips the man and demands to know what he was praying. The man, cowering and in pain, lies to the overlord, saying that it was a Christian prayer. The overlord is satisfied and tells the man he might let him live.

Not only did artwork accompany many feature articles and add to the publication’s creative cachet like no other publication, Majied’s two most iconic drawings appeared on every cover of later editions of Muhammad Speaks, and the other regularly appeared in a center fold. The cover drawing was the outstretched, clasped hands, over the globe of two Black brothers. The centerfold was an illustration of a snake, whose head was the image of Uncle Sam raised over the U.S., with its body wrapped around every continent on earth. “To heal the poisonous bite of the world serpent, it takes the medicine that God gives Muhammad,” declared a caption that accompanied the illustration.

Graphic: Muhammad Speaks/Final Call Archives

|

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!