200 million women, girls have undergone Female Genital Mutilation

By Jehron Muhammad | Last updated: Nov 29, 2018 - 1:53:29 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

Titled “Secular trends in the prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting among girls,” the study drew from two prior surveys that covered nearly 210,000 children in 29 countries between 1990 and 2017.

Recent estimates show that more than 200 million women and children around the world have undergone FGM. The practice of FGM involves removing all or part of a girl or women’s external genitalia, including the clitoris. Many reports suggest the practice in some societies is treated as “a rite of passage.” In a 2003 study, that included Sudanese university students, reported FGM “is usually performed on very young girls by non-medical people and often without anesthesia. Those who survive can suffer adverse health effects during marriage and pregnancy. There are many reasons cited for its performance, among them chastity, increasing chances of marriage, religious decree, and tradition.”

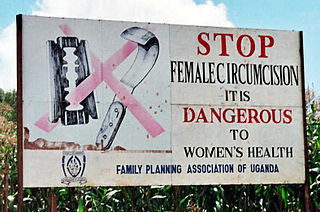

Road sign near Kapchorwa, Uganda, 2004 Photo: wikipedia.org

|

Many Muslims and academics take pains to insist that the practice is not rooted in religion but rather in culture. Haseena Lockhat, a child clinical psychologist, in 2007 in Middle East Quarterly emphasized that when the practice is condemned in much of the Islamic world, “it becomes clear that the notion that it is an Islamic practice is a false one,” she said.

The quarterly said to suggest the problem is localized to North Africa or sub-Saharan Africa is wrong. “The problem is pervasive throughout the Levant (large area covering the Eastern Mediterranean), the fertile Crescent, and the Arabian Peninsula, and among many immigrants to the West from these countries.”

How FGM became attributed to Islam is anyone’s guess. As the discussion in the Sudan study reads with emphasis on vague, “Although there is no explicit mention to female circumcision in the Koran, the Koran forbids causing harm to other Muslims.” Nowhere in the book of guidance to the Muslim world, the Holy Qur’an, is this practice mentioned or sanctioned.

According to a Sudanese legal text, “The law of the Sudan (Vol. 9, 1974-1975) reads: ‘Whoever voluntarily causes hurt to the eternal genital organs of a women is said, save as hereinafter expected, to commit unlawful circumcision. Whoever commits unlawful circumcision shall be punished with imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years or with fine, or with both.” The same provision goes on to exempt those who merely remove the free and projecting part of the clitoris as if the clitoris is not an external genital organ.

In a 2015 report, legal experts demanded a definitive Sudanese law against female genital mutilation. The report published in debangasudan.org mentions a 2012 letter to the United Nations from the Sudanese government saying it was making efforts to formulate a law that prohibits FGM. It claimed to have rolled out a national strategy “to eliminate FGM at federal and state levels of health, education, media, law, religion, and information.”

In 2015 Rashida Manjoo, UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, conducted a 12-day mission to Sudan. Two issues linked to girls were largely focused on: FGM and early marriages.

“The silence and denials, whether by state authorities or many civil society participants, regarding the subject of violence as experienced by women, is a source of concern,” Manjoo noted.

Last year OpenDemocracy.net, in a piece titled “Paper tiger law forbidding FGM in Sudan,” argued while cleverly pleasing “stakeholders” the law failed to protect the very girls who are victims of FGM.

The three co-authors of the piece cited fieldwork they’d done in Khartoum in 2015, where several individuals explained during interviews, “that Islam forbids doing harm to a female’s body and that medical evidence shows that FGM causes extensive damage to women’s bodies and minds.”

They wrote that all the required committees approved the draft law before it was presented to the Council of Ministers. “However, prior to this meeting (they discovered), religious leaders convinced President (Omar) al-Bashir that article 13 was against Sharia, and he subsequently ordered its removal.”

Nafisa Bedri at Ahfad University for Women, reported, “This decision followed a fatwa of the Islamic Jurisprudence Council which called for a distinction to be made between the various forms of FGM.” This fatwa called for a distinction to be made between “pharaonic” circumcision and the “Sunna” type.

Pharaonic circumcision is an assertive act that emphasizes feminine fertility by de-emphasizing female sexuality. This most mutilating kind of FGM called infibulation includes excising the clitoris and labia of a girl or women and stitching together the edges of the vulva to prevent sexual intercourse.

The traditional type of FGM, known as the Sunna Circumcision consists of the removal of the retractable fold of the skin and the tip of the clitoris. One study found, “Ninety-seven (97 percent) of Egyptian girls undergo the Sunna Circumcision. In some West African countries, the tip of the clitoris is removed.”

Despite this setback on a national level, several states including South Kordofan, South Darfur, Dedaref and Red Sea passed laws prohibiting FGM.

The BMJ Global Health study discovered a “huge and significant decline in the prevalence of FGM/C (Cutting) among children aged 0–14 years across countries and regions. This current evidence points towards the success of the national and international investment and policy intervention in the last three decades. One possible explanation in the decrease of FGM/C among young girls (0–14 years) could be the legal ban currently in place in most of these countries, where strong cultural and traditional influence may have acted as an effective deterrent as seen in the decline among these cohorts.”

(Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!