FBI, Lawsuits Could Not Stop Effort To Create Largest Migration In American History

By Erick Johnson -The Chicago Crusader- | Last updated: May 18, 2016 - 11:29:11 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

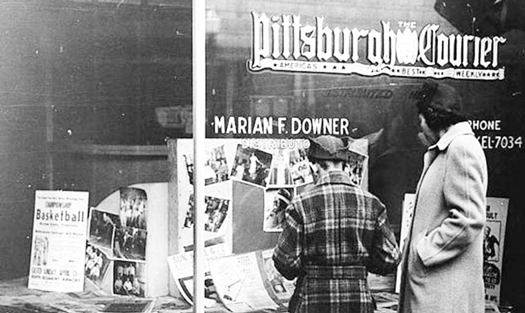

The Pittsburgh Courier’s circulation averaged 500,000 readers weekly during the Great Migration.

|

CHICAGO (NNPA)—There were over six hundred Black families applying for 53 apartment units in just one day in Chicago in 1917. In two years, more than 100 storefront churches would dot the South Side. By 1930 the number would climb to 338. During that time, the Black populations of Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and other major Northern and Western cities would explode as thousands arrived by train almost on a daily basis.

In these cities a Black middle class was established and the largest migration of Blacks in American history swept the nation.

Today, on the 100th Anniversary of the Great Migration, many Blacks in the Midwest and Northeast have parents and grandparents who migrated from the South. Because of direct train routes, Blacks in Chicago are more likely to have parents or relatives from Mississippi. Blacks in New York and Philadelphia are likely to have grandparents from South Carolina. The correlation exists also for other Northern states that were accessible by direct routes that served their Southern states.

"Freedom's Journal" mural outside the offices of the Dallas Weekly, a newspaper that reports on events in the African-American community in Dallas, Texas. Photo: Library of Congress

|

The force behind this movement was the Black Press. And behind the Black Press was the FBI and city officials who aimed to keep Blacks in their place.

Most Blacks who migrated from the South were poor Black men who temporarily left behind families while risking their lives for a future that was uncertain. Their wives and children would stay behind until the men would secure better paying jobs that would support their families.

With little money and the long journey, many did survive the trip. Others were not allowed to board the vehicles by racist train managers. Blacks who did make the trip experienced a side of America that was once off limits to them. Cities that flourished with economic opportunities and better captured the imagination of some six million Blacks, who for the longest time, yearned for prosperity and freedom.

They came from the South, a region whose economy was still struggling from the devastation caused by the Civil War and slavery. For thousands of Black families, jobs opportunities were few. The American dream remained distant and many could not read or write because of the lack of schools in segregated neighborhoods.

When several Black newspapers landed in the hands of many Black Southerners, eyes widened and hopes grew. Headlines and stories that detailed the lives newly planted Black migrants triggered seismic migration and established the Black Press as a significant institution, one that would come under heavy scrutiny as it fiercely advocated the civil rights of Blacks across the country.

The Black Press was around long before the Great Migration, beginning with Freedom’s Journal in 1827. However, historians argue that the Great Migration was a major chapter in history that helped define the Black Press.

In Chicago, many Black men secured jobs as Pullman Porters, which historians say established the city’s Black middle class. Before the mass migration 67 Blacks worked in Chicago’s Union Stockyards, where they slaughtered and processed meat and cattle. After the first migration, the number hovered around 3,000. Most Black Pullman Porters and Stockyard workers were earning higher wages than the jobs they left in the South. On the South Side, the editor of the now defunct Chicago Bee, James Gentry, first coined the named “Bronzeville” because of the newly arrived Blacks from the South. The Chicago Crusader, which originated in the Ida B. Wells housing projects in 1940, published stories that advocated more job opportunities and housing as more Black migrants arrived.

Other Black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Philadelphia Tribune and New York Amsterdam News printed inspiring stories that sparked a migration explosion that began in 1916. Because of the Great Depression, the movement would cool before thousands more would move North between the 1950s and 1970s. One hundred years later, historians and residents today are marking the milestone with celebrations and seminars to educate a young generation whose parents and grandparents likely migrated from the South.

White newspapers during the Great Migration did not print stories about Blacks or their progress. The newspaper that has been widely credited for sparking the Great Migration is the Chicago Defender, a newspaper that was started with just 25 cents by Robert Sengstacke Abbott in 1905. Because of racism, Abbott, a native of Savannah, Ga., was unable to establish a law practice in Chicago and Gary, Ind. After he founded the paper in the kitchen of his landlord’s apartment, Abbott wrote scathing editorials against racism and ran stories that highlighted the success of Blacks migrants in Chicago. He urged readers to leave the South and posted job listings, train schedules, and photos of the best schools, parks and housing in the city, in comparison to the deplorable conditions in the South.

Because of its coverage, the Defender gained a heavy readership. According to various news reports, the paper was read aloud during church services, in barbershops, homes and on the streets. With stories on Black culture, weddings and lifestyles, the Defender became a must read for Blacks. The paper’s readership went from 10,000 in 1916 to 230,000 in a week. During that time, as many as four readers reportedly shared a copy of the Defender.

Some White newsstands refused to carry the paper. In Mississippi, one county banned the Defender, declaring it “German propaganda.” In Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the city sued to get an injunction to prohibit the circulation of the Defender. Eighteen Black leaders including two ministers were named defendants in the lawsuit. In addition, the FBI began spying on the Defender six months before World War I, according to the Black Press Research Collective, a group of scholars who posted the report in March 2013. The report said the government kept a “vigilant watch” over the Defender and several Black newspapers, which were feared of having ties to the Communist Party.

The Atlanta Independent, a defunct newspaper that ran from 1903 to 1928, was also prohibited from being circulated.

Despite the challenges, the Defender still flourished. A shrewd businessman, Abbott by 1920, employed 563 newsboys to sell his paper on the street. In Southern states, Black Pullman Porters from Chicago smuggled the paper on the trains and dropped them off to a pickup person. Many did so while risking their jobs and lives. They were also carried in churches, barbershops and Black businesses. In the early twentieth century, the Defender was the best-selling Black newspaper in the country.

Another banned Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier (now the New Pittsburgh Courier), used the Black Pullman Porters to carry out its “Stop and Drop” campaign, where a bundle of papers were dropped before they were sold.

The Courier’s readership also skyrocketed. With papers in fourteen major cities, the Courier’s weekly circulation peaked at 500,000, according to news reports.

Today, the Black Press is faced with new challenges and opportunities. With race relations back in the nation’s spotlight, the Black Press is poised to bounce back after years of declining readership. There are also fading job opportunities in the North that are fueling what many are calling a reverse migration. Many Blacks whose parents and grandparents moved to the North are heading back South. According to the U.S. Census, between 2000 and 2010, an estimated 1,336,097 Blacks moved to Southern cities alone, according to the Brookings Institute, which based the study on recent U.S. Census data.

In 2011, Atlanta overtook Chicago as the city with the second largest Black population. Chicago is number three while New York maintains the top spot.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!