Celebrating the life and the gift of Mayor Marion Barry

By Askia Muhammad and Nisa Islam Muhammad Final Call Staffers | Last updated: Dec 9, 2014 - 5:38:02 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

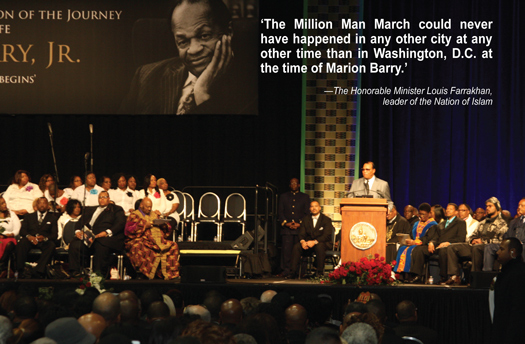

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan speaks during the funeral service for Marion Barry Dec. 6, in Washington, D.C. Local and national political leaders, prominent clergy and D.C. residents who got their first job as a result of Marion Barry’s programs were among the thousands who gathered at the Washington Convention Center to say goodbye to the man dubbed “Mayor for Life.” Photo: Hassan Muhammad

|

WASHINGTON (FinalCall.com) - After a joyous, but dignified memorial service attended by thousands of Washingtonians Marion S. Barry, Jr. was quietly and solemnly laid to rest at the Congressional Cemetery by 50 tearful family members and supporters Dec. 6.

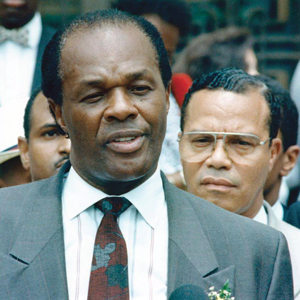

Mayor Marion Barry (March 6, 1936 - Nov. 23, 2014). Photo: AP/Wide World Photos

“A man can choose to escape and forget childhood poverty and merely reminisce about his early years in the movement. Instead, Marion joined his childhood poverty and his life-changing years in the civil rights movement to form his world view.” –Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton |

“The Million Man March could never have happened in any other city at any other time than in Washington, D.C. at the time of Marion Barry,” the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam said in a stirring tribute to the man he called a “friend” and “companion” in the struggle to uplift Black people.

Mr. Barry was “Not just a local figure,” the Muslim leader continued. “His work was national and international.” Mr. Barry was “a man who loved God and loved the people of God. Some of us who come into this life are called not just to work for their family,” Minister Farrakhan told Mr. Barry’s 34 year-old only child Marion Christopher Barry, “but for a higher calling.”

“And like everyone born on this earth, he made errors, he committed sins,” Minister Farrakhan said, addressing Mr. Barry’s controversial arrest on drug charges after a $40 million federal investigation and sting operation. “In this world, when you do good for the masses, you are not loved by those who suck the blood of the masses.”

Mr. Barry died early Nov. 23, of apparent natural causes, after being released just hours earlier from the hospital. Mr. Barry battled kidney problems stemming from diabetes and high blood pressure and underwent a kidney transplant in February 2009.

Mayor Marion Barry stood strong in support of the Million Man March with the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in Washington, D.C., 1995.

|

Mr. Barry was first elected mayor in 1978 after building a political career as an activist-organizer and the first chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and as a local activist in Washington. He was re-elected in 1982 and 1986, and again in 1994.

Mr. Barry has joined the pantheon of civil rights leaders who died before him, the Rev. Jesse Jackson said, in a eulogy at the end of the four-hour service. “Marion was one of the architects of the New South and the New America,” pointing out that when he came to Washington in the 1960s, segregation was still in force and Blacks were denied the vote all over the South.

In Mr. Barry’s wake, the New South is full of skyscrapers, and professional athletic teams full of Black athletes competing from Georgia, to Tennessee, to Florida, to North Carolina, the Rev. Jackson said. “Marion Barry emancipated Washington,” and the South, he continued.

After a humble beginning in which he chopped cotton on a plantation in his hometown of Itta Bena, Mississippi, then selling newspapers on the streets of Memphis, Mr. Barry left college in 1960 just before he completed his Ph.D. in chemistry to work in the civil rights movement, then rose to become mayor of the capital city of the United States.

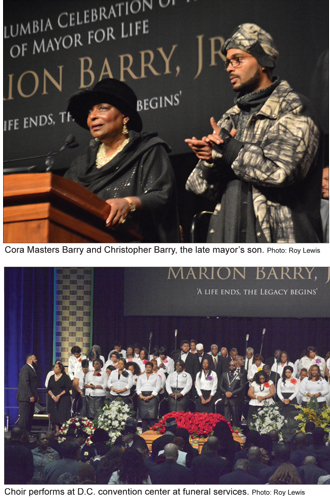

For his part, Mr. Barry’s son, thanked his father for teaching him life lessons, including a formative trip to Barry’s native Mississippi when he was 13. He said Barry wasn’t a conventional father, but he always felt the love Mr. Barry had for his constituents. “I didn’t always feel like he had the time to spend with me as a father,” Christopher Barry said. “It was other people that embraced me. I never felt his absence because I always felt his love through others.”

|

Minister Farrakhan said he was asked by a reporter at the time—who praised him before her question for being a devout Muslim who did not drink or smoke—what he thought of a man who broke his marital vows and used drugs. “I said, ‘Who are you talking about, John Fitzgerald Kennedy?’ That ended the press conference,” the Muslim leader said to a raucous ovation.

“They hide the wickedness of their own leaders. Nobody passes this life without committing sin. When I say nobody, I mean nobody. The popes, the cardinals, the imams, the mullahs. If I did not commit sin, I would not need the mercy of God,” Minister Farrakhan continued. “The Holy Qur’an says, ‘If Allah were to punish man for his sins, none would be left.’ So will the holy ones stand up?” At that time everyone the dais, the choir members and all the dignitaries who were on their feet cheering the Minister’s remarks sat down. “This is not a sad moment. Celebrate the life of a man who made life better.”

Mr. Barry was remembered as a man who was shaped long before he came to Washington, by his organizing work in the South.

“In speaking about Marion as a son of the civil rights movement, I speak not only for myself. I speak in memory of someone who knew and worked with Marion but have passed on,” said Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, “for others of his movement colleagues, who wanted to be here but could not, and for still others who are here.

“The roll of those who first worked with Marion in the movement is too long to call, but among them are and were John Lewis, Frank Smith, Joyce and Dorie Ladner, Bob Moses, Julian Bond, Ruby Robinson, Courtland Cox, Chuck McDew, Diane Nash, James Foreman, Stokely Carmichael, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Gloria Richardson, Bernard Lafayette, and Rev. Jesse Jackson.”

“You have come a long way, buddy, from picking cotton in Itta Bena, Mississippi to running the nation’s capital,” Mrs. Norton said she often reminded Mr. Barry. “But those cotton picking roots served Marion Barry Jr. well. He challenged poverty by working himself out of it. ‘Coming from the cotton fields of Mississippi, I was used to hard work. It doesn’t bother me,’ he wrote in his autobiography. But, it was the civil rights movement that equipped Marion to challenge segregation and prepared him to become our mayor.

|

That world view, that insistence on using the levers of power to better the lives of ordinary people—the elderly, the young, the formerly incarcerated—made him much beloved by the people of Washington, and was responsible for creating one of the best educated, wealthiest Black middle-class communities in the world.

Countless people in the audience and on the dais, including Rushern Baker, the chief executive of neighboring Prince George’s County, Md., credited Mr. Barry’s Summer Youth Leadership Program—which guaranteed a job for every Washington teenager who wanted one—with providing them their first employment opportunity.

His insistence that D.C. government contracts be given to non-White-owned businesses, and that developers include non-White partners in their projects also created countless millionaires. When he was elected mayor in 1979, Blacks received only 3 percent of D.C. government contracts. After his last term, that portion had increased to 50 percent.

Billionaire real estate developer R. Donahue Peebles—the largest Black real estate developer in the country—said he owes all his success to Mr. Barry, who appointed him to a city real estate board at age 24 and helped him start his business.

“Marion Barry taught me to dream big. Marion Barry gave me the opportunity to make those dreams come true,” Mr. Peebles said. “Marion Barry made Washington, D.C., the Mecca of African-American entrepreneurship. Marion Barry created the Black middle class in Washington, D.C.”

“Marion Barry was an icon. He was the consummate politician. He was an elder statesman. He was a fierce fighter for the dispossessed,” said the Rev. Willie Wilson, Pastor of Union Temple Baptist Church, one of the national co-chairs of the Million Man March, and one of several clergy who ministered to Mr. Barry over the years.

While Mr. Barry made it possible for many Blacks in Washington to become wealthy, he never stole one dime, nor did he even take anything of substance for himself. One speaker recalled that when asked why ordinary citizens were so loyal to him, a man told a reporter: “I know that if there’s just one dollar on the table, Marion Barry will fight to see that we common people will get part of that dollar.”

Mr. Barry lived and was remembered for always adhering to his self-declared creed, to serve “the last, the lost, and the least.”

The life of the man many called the city’s greatest politician was celebrated with a variety of events that included a rally, a 24-hour viewing, children releasing balloons, a processional through the city, a community memorial service and a funeral at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center for thousands.

Audience at D.C. civic center responds during Barry memorial service. Photo: Roy Lewis

|

Mayor Barry, who died Nov. 23, at the age of 78, served the city in a range of capacities including being mayor for 16 years and serving as a city councilman for another 16 years. He died representing the poorest section of the city, Ward 8 on the Southeast side of the city.

A celebration of his life started Dec. 1, when ex-offenders, known in the city as returning citizens held a rally and march. Sponsored by activist groups Cease Fire Don’t Smoke the Brothers and Sisters and Universal Madness, the march featured all those who served prison time carrying an empty coffin throughout the city chanting “Marion Barry! Mayor for Life!”

Mayor Barry was instrumental in decreasing the discrimination against ex-offenders.

“Mayor Barry helped me tell the truth on my job application for the first time,” said Jason Roberts, who was incarcerated for 10 years and desperately needed to find a job when he returned to the city. “I was always scared they would find out I was a felon. What Barry did lifted a burden. I committed a crime and paid my debt to society. Many couldn’t forget that, Barry could and he gave us another chance.”

Official services for Mr. Barry kicked off December 3, when his body was brought to the Wilson Building by an honor guard where it lay in repose for 24 hours for public viewing. Services started with a short 15 minute ceremony after the family was seated followed by many of those whose lives were changed by Mayor Barry.

Later that day all of the schools in Ward 8 took time to have students remember Mayor Barry who also served on the D.C. school board in his early days. Students released balloons as they said farewell to Mr. Barry.

His body was placed in a hearse Dec. 4 and a processional through the city gave people who lined the streets an opportunity to say their final farewell. When the body arrived in Ward 8, it was transferred to a horse drawn carriage that took it to Temple of Praise Church for another public viewing and community memorial service.

“Marion Barry, mayor for life, did so much for so many. He appointed two ex-offenders to the parole board,” said Tyrone Parker, founder of the Alliance for Concerned Black Men before a standing-room only crowd. “He just did so much for us. We will become the vanguard for our families and communities. He offered us compassion and redemption as we attempted to reshape our lives.”

Rev. Wilson told the crowd how the mayor for life started the Capital Area Food Bank in 1980, which provided 30 tons of food each year. “He was responsible for over a billion meals,” said Rev. Wilson.

Follow Final Call senior editor Askia Muhammad on Twitter: @askiaphotojourn. Follow Final Call staff writer Nisa Islam Muhammad on Twitter: @nisaislam.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!