Agent provocateurs? ‘Revolutionary’ Whites try to incite unarmed crowd in Ferguson, Mo.

By Richard B. Muhammad | Last updated: Aug 19, 2014 - 8:12:07 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Col. Ron Replogle, left, and Capt. Ron Johnson talk with Malik Shabazz, president of the Black Lawyers for Justice, (center) during a march with protesters along W. Florissant Avenue in Ferguson Missouri on, Aug. 16

|

FERGUSON, Mo. - The National Guard has rolled in, but the pain and passion of people in the streets, in homes and in businesses remain and broken hearts still ache.

Tear gas, rubber bullets, gas masks, gas canisters and armored trucks have been deployed at night along Florissant Avenue, where demonstrators marched, sang, grieved, clapped, hugged and cried.

There was a new order before and after sundown Aug. 18, the day the Guard arrived, though security was still overseen by the state highway patrol. The new tactic was to keep everyone moving on the sidewalks and no cars were allowed to drive down the street.

“Hands up! Don’t shoot!” was the cry of crowds, parents and children. “No justice, no peace!” shouted demonstrators expressing anger and anguish over the killing of a Black teenager, a heavy-handed police response, and what many saw as agitation by law enforcement. They walked up and down streets in a designated protest area. No one was allowed to stand still.

Protesters fill Florissant Road in downtown Ferguson, Mo. Aug. 11, marching along the closed street. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

By about 10 p.m., a White man with a gray ponytail, who was part of a group wearing shirts with slogans about revolution tried to rally people in the middle of the street. “We have the right to protest!” he shouted. “You can’t tell us how to protest!” The group was about four or five people and police put on gas masks. Then armored vehicles started to move forward, blocking the street, telling people to get out of the street.

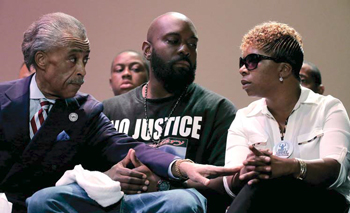

Rev. Al Sharpton, left, speaks with parents of Michael Brown, Michael Brown Sr. and Lesley McSpadden, right, during a rally at Greater Grace Church, Aug. 17, for their son who was killed by police last Aug. 9 in Ferguson, Mo. Sharpton told the rally Brown’s death was a "defi ning moment for this country."

|

“We stopped it, we told them you go somewhere else and do that,” continued the longtime St. Louis activist and advisor to the family of Michael Brown, an unarmed youth gunned down by a Darren Wilson, a White officer with the Ferguson Police Dept.

The instigators wanted to exploit hurting Black youth, who saw the killing of Michael Brown as the last straw, seeing his body in the street, and the police put dogs on us after gunning the 18-year-old down, said Mr. Shaheed. “You don’t think we are sensitive to our own suffering?” he asked.

The young people need jobs, training, trades and warrants cleared, you would not have problems if you solved these things, said Mr. Shaheed. “I am not denouncing this young Black man, my job is to get in the street and help him. If they had not did what they did the world’s attention would not be here.”

Malik Shabazz of Black Lawyers for Justice yelled at the protestors to back away from police officers through a bullhorn. Black clergymen, in collars and without, waded into the crowd; they formed a line between the crowd and the officers. A young pastor who was part of the Peacekeepers group worked to quash the conflict.

Activist Zaki Baruti of the St. Louis-based Universal African Peoples Organization also walked the streets just before the clash.

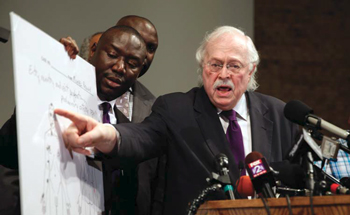

Former New York City chief medical examiner Dr. Michael Baden, right, speaks as Brown family attorney Benjamin Crump, left, holds a diagram produced during a second autopsy done on 18-year old Michael Brown, Aug. 18, in St. Louis County, Mo. The independent autopsy shows Brown was shot at least six times. Photos: AP/Wide World photos

|

“There is nothing going on that merits this scene out of Bragam,” said CNN reporter Jake Tapper, referring to the war in Iraq. “This doesn’t make any sense.” He had cameras pan to show how far away protestors were from heavily armed police. The police are not facing a threat, he said.

The crowd applauded and raised their arms shouting, “Hands up, don’t shoot!” as the tension faded and officers retreated to their vehicles.

“We are not going to allow infiltrators to destroy this movement,” said Mr. Shabazz. “We’re not going to see women get hurt. I am not going to see this end in a disaster tonight.” They are plants who are not with us, he said. “We need more men to step up and keep the peace. These kids will listen to us,” Mr. Shabazz said during a live interview with CNN. These infiltrators have been out here every night trying to incite people against the police and destroy this movement, he said.

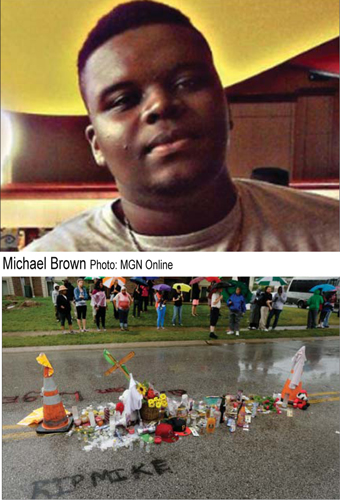

People gather next to a makeshift memorial for Michael Brown, Aug. 16, located at the site where Brown was shot by police in Ferguson, Mo. Brown’s shooting in the middle of a street following a suspected robbery of a box of cigars from a nearby market has sparked a week of protests, riots and looting in the St. Louis suburb.

|

The burned out gas station and convenience store had been a mecca for protestors, speakers on bullhorns and a refuge when rain struck. There were also reports of other clashes and tear.

When the governor sent in the National Guard, he lifted the 12 midnight to 5 a.m. curfew.

Fear, humiliation and anger

“Women, babies, children screaming, yelling—and those smoke bombs were in these babies’ faces trying to flee from the smoke,” said Paulette Wilkes, a mother of two sons and a St. Louis school teacher, of on the outbreak the night before the National Guard arrived. Protestors said a midnight curfew was revoked after tension between officers and protestors escalated. There wasn’t violence but young people were upset, said Ms. Wilkes.

She has seen the humiliation of Black youth and Black people in St. Louis. She sees youth fed up and willing to die to stand against oppression.

“He was just walking along and talking, the next thing I know the police rushed him and threw him to the ground. The crowd ran over and shouted don’t shot, don’t shoot,” Shay Watts told The Final Call as an incident quickly unfolded around 9:30 p.m. on Aug. 18.

County cops and state troopers don’t know how to interact with this neighborhood or Black people, said the Ferguson resident.

|

“They are too aggressive toward us, if you come to somebody with that attitude they are going to give the same thing back. These men out here feel disrespected, especially the Black men,” said the 44-year-old woman. “I don’t think it’s going to end well, it’s just not the same feeling as it was early yesterday. We feel like they are trying to sabotage Capt. Johnson.”

“When the police antagonize them (youth) say they will die for the same streets they should have the right to walk up and down,” she said. Her 23-year-old son agrees with other young people telling her, “the police don’t care about us.”

“You don’t just wake up today angry. Something has made you angry. That was when that police talked to you like you was a ‘boy,’ or like you was a child these are grown young men that should be talked to as such,” she added.

A major reason for Ms. Wilkes and thousands at ground zero Sunday evening Aug. 17 was a positive church gathering at Greater Grace Church featuring Rev. Al Sharpton, Martin Luther King III, TV judge Greg Mathis, actress Keke Palmer and state highway Capt. Ron Johnson, who was put in charge of security by Gov. Jay Nixon, who sat down the White chief of police in Ferguson.

Capt. Johnson, who is Black and grew up in the area, pulled back from the heavy military armored vehicles and heavy weapons. He engaged the community, answered questions from the media and ordinary people and eased tension.

Missouri State Highway Patrol Capt. Ron Johnson speaks during a rally at Greater Grace Church, for Michael Brown Jr., who was killed by police Aug. 9 in Ferguson, Mo.

|

But in wee morning hours Monday, he reported protestors had tried to march to the police staging area another officer said protestors tried to storm the command center.

There was late night conflict the weekend of Aug. 15, 16, 17, a Friday, Saturday and Sunday night. There was sporadic looting but few arrests. The first night of the curfew most people left. Some 150 people broke the curfew with a White revolutionary group inciting the crowd. There were seven arrests. One person was reported shot that Saturday night. It was reported that one curfew breaker protestor shot another, likely in the midst of teargas.

But the policing was not without problems, said Shay Watts who watched an arrest of two young Black males around 9:30 p.m. on Aug. 18. Blacks have complained Ferguson’s three Black officers despite a 67 percent Black population and abusive police was the norm for small hamlets in suburban St. Louis, but the city also has problems.

Holly Hodges stood across the street from Ferguson police headquarters with a huge portrait of her brother on one arm and Jaden, her seven-year-old nephew, on the other. The 39-year-old St. Louis resident said her brother was shot and killed by police Jan. 8, 1996. A grand jury declined to file criminal charges against officer Heriberto “Eddie” Sanchez, who resigned after the fatal shooting of Garland Carter.

Her brother was unarmed, the officer dropped a weapon to frame Garland and got away with it, she said. Her brother was 17-years-old at the time.

A call for dialogue with youth

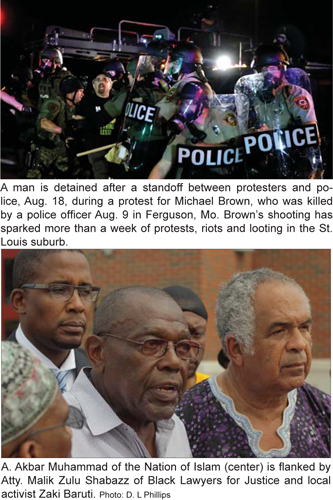

Abdul Akbar Muhammad of the Nation of Islam, Mr. Baruti of the Universal African Peoples Organization, Atty. Shabazz of Black Lawyers for Justice and other activists stood outside the Ferguson Police Department headquarters and called for a town hall meeting with youth and restraint from law enforcement and the National Guard. They also called for a five-day moratorium on night protests.

The activists called for major racial sensitivity retraining for officers and pointed out studies show Blacks are disproportionate victims of police stops, something Blacks bitterly complained of.

They were among grassroots activists and members of the Fruit of Islam who helped keep the peace Aug. 14, which was a night without residents.

While there were some looting incidents in the evening, which activists say are connected to police provoking crowds by simply showing up or even calling protestors animals or monkeys.

A looter escapes with items from Feel Beauty Supply on West Florissant Avenue in Ferguson early, Aug. 16, after protestors clashed with police.

|

Quan, 16, was hurt by the death of “Big Mike” who he called a friend of his older brother. He feels the anger but doesn’t want to attack police. He is a junior in high school. His girlfriend is three months pregnant. He is trying to stay out of trouble, get ready for a child and have a future. He wants help. Police officers have harassed him and others and he is tired of it.

The president speaks

In a message Aug. 18, President Obama said he understands pain and anger but it should not result in looting, carrying guns or attacking police. That undermines justice, he said. But constitutional rights to assemble, speak freely and freedom of the press should be respected, said President Obama, in his second public statement.

The Justice Dept., the FBI and state officials are probing the crime. It was reported Aug. 18 that Attorney General Eric Holder was coming to Ferguson.

Results from a private autopsy were revealed at Greater St. Mark Family Church Aug. 18 by attorneys Ben Crump and nine days after the death of Michael Brown. That autopsy found the victim was shot at least six times and suffered two head wounds, according to Dr. Michael Baden, former New York City chief medical examiner and forensic pathologist Shawn Parcells, who assisted with the private autopsy. Mr. Brown’s right arm was grazed by a bullet, which could have meant his back was to the shooter, or his arm was swinging. Other wounds could have meant his hands were in a defensive position over his chest or face, said the men who conducted the autopsy.

The Associated Press reported evidence could be reviewed in a few days “to determine whether the officer, Darren Wilson, should be charged in Brown’s death, said Ed Magee, spokesman for St. Louis County’s prosecuting attorney. According to the Associated Press, the St. Louis County medical examiner’s autopsy found that Mr. Brown was shot six to eight times in the head and chest and full autopsy findings could come by the end of August or early September.

The preliminary autopsy confirms witness accounts, Atty. Ben Crump told reporters. The police could have shared this early, instead of trying to smear the victim’s reputation by accusing him of a strong arm robbery, said lawyers for the Brown family.

The family had no confidence in what the county “was going to be put in the reports about the tragic execution of their child,” said attorney Crump.

According to Dr. Baden, a bullet entered the victim’s skull, and signifies his head was forward when the kill shot struck him. He was also shot four times in the right arm but there was no gun-power residue on Mr. Brown’s body, so it was unlikely he was shot up close.

(Jihad Hassan Muhammad and A.J. Salaam contributed to this report.)

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!