Troubling rise in Black children pushed into adult court

By Barrington M. Salmon -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Oct 24, 2018 - 11:18:35 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Study shows increase in youth in adult courts, jails at highest rates in the last 30 years

|

Mass incarceration could be likened to a disease that has fractured, ravaged and weakened Black communities for decades. Critics of the criminal justice system point to the 1.5 million Black men who have been locked up, the increasing number of women being jailed, the long-term and lasting effects on those who are incarcerated, their families and the wider community, as well as the decimation of Black communities nationwide.

Studies show that the children of incarcerated parents face pro-found and complex threats to their emotional, physical, educational, and financial well-being. Because of imprisonment, families are torn apart, children grow up without their fathers and mothers; children generally fall behind in school, experience anxiety, and according to a number of studies, exhibit other problems, such as depression, shame, guilt, withdrawal and hypervigilance.

Yet another part of the problem affecting Blacks is the overwhelming number of Black children who are sent to adult prisons and jails.

A new report, “The Color of Youth Transferred to the Adult Criminal Justice System: Policy and Practice Recommendations,” discusses “how the egregious practice of prosecuting and incarcerating Black youth as adults— which is rooted in our nation’s past and ongoing racism—has had a devastating impact on Black children and young adults and the Black community.”

Jeree Thomas, co-author of the report, “The Color of Youth Transferred to the Adult Criminal Justice System: Policy and Practice Recommendations,”

|

Jeree Thomas, co-author of the report with Mel Wilson, said she continues to be troubled by the fact that while juvenile arrest rates have fallen sharply in recent years, Black youth are disproportionately sent to adult court by judges at some of the highest percentages seen in 30 years.

“We’re seeing it in the numbers. The disproportionality has gone up, the percentage of Black kids has gone up,” said Ms. Thomas, policy director of the Campaign for Youth Justice. “Looking at 30 years’ worth of data, the percentage of those being transferred who are Black has gone up. It is compounded by more Black children being arrested by law enforcement and being treated as adults.”

“What we see is the compounding of individual and systemic bias within a historical and social context to the ideas of Black children being less innocent and less childlike. This is a historical narrative of how Black children are perceived. Black boys and girls are viewed as less innocent and older.”

Ms. Thomas said she and Mr. Wilson looked specifically at Oregon, Florida and Missouri because those states have interesting histories around juvenile justice and have been trying to address this issue.

“And they were pretty transparent with their data,” she said.

Race, implicit and explicit racial bias and America’s history of its treatment of Blacks continues to play an outsized role in who ends up behind bars, she said.

“What I tell people is that there are both individual and systemic problems. Some people who make laws have bias. And that can be seen in how laws are written,” said Ms. Thomas. “For example, in a number of states, they are trying to enhance gang punishment. When they think of gangs, they’re not defining White supremacist gangs, so kids in White supremacist groups will never be added to the gang database. Kids of a certain color are affected. This is all geared towards the criminalization of Black kids. It’s a complex issue—affected by historical bias (intentional or not) who’s being policed and the resources that are made available. So much is built on this rotten foundation.”

Richmond, Virginia native Da’Quon Beaver knows the perils of being jailed as a child from personal experience. He is a formerly incarcerated individual, now a Campaign for Youth Justice spokesperson and advocate, whose life was directly and almost irrevocably affected after being sentenced as a child to adult prison.

“I was incarcerated at the age of 14 for a robbery charge, me and five individuals. I was the youngest in the group,” he recalled in a Campaign for Youth Justice video about his experiences. “I was certified as an adult, which means I had to go to circuit court not juvenile court and was sentenced to 48 years. I served five as an adult. I told my mom that when I was sentenced to 48 years, I felt like I was forced to be a man right there in the courtroom because I got ‘grown man’ time.”

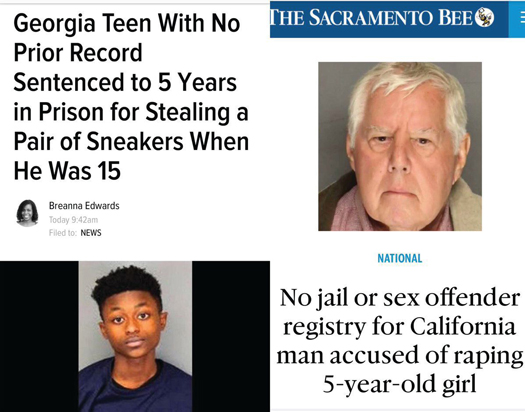

Observers say Black boys are at the highest risk for harsh sentencing for misdemeanor offenses.

|

Mr. Beaver, 25, who works as a community organizer, agrees with advocates that adult prisons are no place for children and teens.

“So I do not think that the adult system is anywhere for a kid, because the key word is ‘adult,’ ” he said. “I personally know that a lot of, especially boys, they get to 14, 15 and are like ‘I’m a grown man, I’m a grown man,’ but realistically your mind does not stop developing until after 21, for a guy 22. You have kids who may have the physical build but mentally are not ready for adult system. They still need education, still need someone to talk to—they still haven’t finished developing.”

Mr. Wilson agrees.

“Research has proven that adult courts and jails are no place for children—the brain development of youth is markedly different from adults and they are more prone to risk taking and not thinking through the consequences of their actions,” said Mr. Wilson, Social Justice and Human Rights manager for the National Association of Social Workers. “Youth involved in the justice system are also more likely to have mental health needs and have suffered from trauma so they need rehabilitation and treatment services that are not provided in most adult jails.”

Ms. Thomas and Mr. Wilson contend advocates seeking to understand and reduce disproportionate representation of Black youth in the adult criminal justice system must start by looking through the lens of the Thirteenth Amendment. Black youth are approximately 14 percent of the total youth population, but 47.3 percent of the youth who are transferred to adult court by juvenile court judges who believe the youth cannot benefit from the services of their court.

Further, Black youth are 53.1 percent of young people transferred for person offenses despite the fact that Black and White youth make up an equal percentage of youth charged with person offenses, 40.1 percent and 40.5 percent respectively, in 2015. Researchers, system stakeholders, and advocates have reported on the disproportionate representation of Black youth at nearly every contact point in the juvenile justice system. Some research indicates that even when accounting for the type of offense, Black youth are more likely to be sent to adult prison and receive longer sentences. Although stakeholders acknowledge these findings, they are rarely contextualized beyond the justice system, they said.

Ms. Thomas said there isn’t much data on this issue broken out by race, although she cited a report, titled Getting to Zero, by UCLA law professor and researcher Neelum Arya, who estimates that between 32,000 and 60,000 youth go through adult jails every year. That figure, however, doesn’t include prison numbers. Bureau of Justice statistics only provide one-day counts and no data by race of young people in adult prisons and jails, Ms. Thomas explained.

Studies abound detailing the disproportionate treatment of Black boys and girls by schools, law enforcement and the criminal justice system and the myriad of consequences.

“I was incarcerated at the age of 14 for a robbery charge, me and five individuals. I was the youngest in the group,” he recalled in a Campaign for Youth Justice video about his experiences. “I was certified as an adult, which means I had to go to circuit court not juvenile court and was sentenced to 48 years. I served five as an adult. I told my mom that when I was sentenced to 48 years, I felt like I was forced to be a man right there in the courtroom because I got ‘grown man’ time.”

Mr. Beaver, 25, who works as a community organizer, agrees with advocates that adult prisons are no place for children and teens.

Georgia governor candidate Stacey Abrams is a strong proponent of children’s rights.

|

“So I do not think that the adult system is anywhere for a kid, because the key word is ‘adult,’ ” he said. “I personally know that a lot of, especially boys, they get to 14, 15 and are like ‘I’m a grown man, I’m a grown man,’ but realistically your mind does not stop developing until after 21, for a guy 22. You have kids who may have the physical build but mentally are not ready for adult system. They still need education, still need someone to talk to—they still haven’t finished developing.”

Mr. Wilson agrees.

“Research has proven that adult courts and jails are no place for children—the brain development of youth is markedly different from adults and they are more prone to risk taking and not thinking through the consequences of their actions,” said Mr. Wilson, Social Justice and Human Rights manager for the National Association of Social Workers. “Youth involved in the justice system are also more likely to have mental health needs and have suffered from trauma so they need rehabilitation and treatment services that are not provided in most adult jails.”

Ms. Thomas and Mr. Wilson contend advocates seeking to understand and reduce disproportionate representation of Black youth in the adult criminal justice system must start by looking through the lens of the Thirteenth Amendment. Black youth are approximately 14 percent of the total youth population, but 47.3 percent of the youth who are transferred to adult court by juvenile court judges who believe the youth cannot benefit from the services of their court.

Further, Black youth are 53.1 percent of young people transferred for person offenses despite the fact that Black and White youth make up an equal percentage of youth charged with person offenses, 40.1 percent and 40.5 percent respectively, in 2015. Researchers, system stakeholders, and advocates have reported on the disproportionate representation of Black youth at nearly every contact point in the juvenile justice system. Some research indicates that even when accounting for the type of offense, Black youth are more likely to be sent to adult prison and receive longer sentences. Although stakeholders acknowledge these findings, they are rarely contextualized beyond the justice system, they said.

Ms. Thomas said there isn’t much data on this issue broken out by race, although she cited a report, titled Getting to Zero, by UCLA law professor and researcher Neelum Arya, who estimates that between 32,000 and 60,000 youth go through adult jails every year. That figure, however, doesn’t include prison numbers. Bureau of Justice statistics only provide one-day counts and no data by race of young people in adult prisons and jails, Ms. Thomas explained.

Studies abound detailing the disproportionate treatment of Black boys and girls by schools, law enforcement and the criminal justice system and the myriad of consequences.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!