Richard Hatcher, former Gary, Ind., mayor passes

By The Final Call | Last updated: Dec 17, 2019 - 7:52:54 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

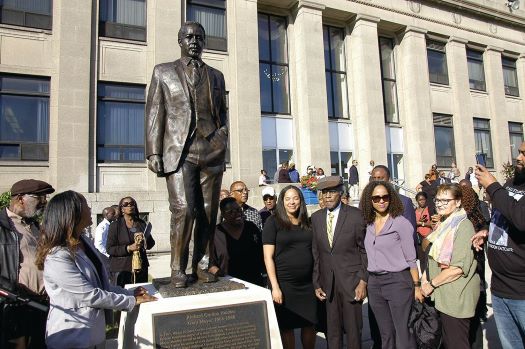

Former Mayor Richard Gordon Hatcher at right in hat stands with family members and admirers at Oct 9 at unveiling of statue in his honor outside city hall.

|

CHICAGO—The man who made history as the first Black big city mayor has died and will be remembered for his leadership in Gary, Ind., and an historic Black political convention hosted in his city.

Mayor Richard Gordon Hatcher, who passed away Dec. 13 in a Chicago hospital, was 86-years-old, said his family in a statement.

Mayor Hatcher, who was elected in 1967, was surrounded by his family and loved ones “in the last days of his life” the statement said.

“While deeply saddened by his passing, his family is very proud of the life he lived, including his many contributions to the cause of racial and economic justice and the more than 20 years of service he devoted to the city of Gary,” the family added.

Mr. Hatcher served 20 years as mayor, and convened the historic 1972 Black Political Convention.

Several weeks ago, the mayor was honored with the unveiling of a statue in his honor outside Gary’s city hall and was lauded for his decades of service.

Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan called Mayor Hatcher a “companion in the struggle” at the statue unveiling.

Mayor Hatcher was remembered as a civil rights activist, lawyer, trailblazer, father, history maker at the Oct. 9 ceremony featuring his bronze statue.

He was described as a man who fought to improve the conditions of Black residents long neglected by the city’s White establishment and to revive a city as de-industrialization ravaged the city’s steel mills.

Mr. Hatcher won his 1967 election in a time when the nation was in the throes of a Black consciousness revolution with the rise of the civil rights and Black Power movements. Cleveland elected its first Black mayor with Carl Stokes the same year. But Mr. Hatcher’s election paved the way for hundreds of other Blacks to lead major cities some 50 years later, said admirers.

“My friend, brother, leader, teacher, companion in the struggle and a guide to us all,” said Minister Farrakhan at the October gathering outside city hall in Gary, Ind. He called Gary “the great city that fell down, but a great city that can’t stay down because of the leadership that God has put here. And if we follow in the footsteps of Mayor Hatcher, the city will once again be one of the great cities in North America.”

Minister Farrakhan didn’t mince words when he described the impact Mr. Hatcher’s leadership had on dismantling the White Democratic machine’s grip on Gary that kept its Black residents segregated, political castrated and disenfranchised.

“Richard Gordon Hatcher has been a servant not only to the Black community, but he struggled to make other communities more humane in how they dealt with the underprivileged and the forgotten,” the Minister said.

Min. Farrakhan and former Mayor Richard Hatcher at unveiling of statue outside city hall in Gary, IN. Mayor Hatcher died Dec 13 at 86 years old.

|

He offered analogies between the former mayor, who he called a servant, and the example of Jesus. Minister Farrakhan said both were persecuted for their efforts to help the poor.

In 1967, Mr. Hatcher won the Democratic Party primary when two White candidates including the incumbent split the White vote. Mr. Hatcher then went on to win the general election even though the Democratic Party supported his White Republican challenger.

His administration attracted national attention as well as federal dollars. With the funds, Mr. Hatcher established anti-poverty programs, improved housing, health care and gave disadvantaged youth jobs and after school activities. Even before he was elected mayor, Mr. Hatcher served on the city council where he worked to tear down institutional and structural racism that kept Blacks out of the central business district and corralled into the city’s midtown section.

His efforts riled the city’s shrinking White population who eventual fled, taking tax dollars with them to establish the town of Merrillville, just outside of Gary. The enmity of being the first Black mayor of a city with a population of over 100,000 radiated from all level of governments. Mr. Hatcher’s own city council chamber fought him on key policy issues.

Mayor Hatcher, Minister Farrakhan said, never lost sight of his principles. His legacy will long outlast the bronze statue molded to resemble the former mayor in his younger days, he added. “The grave can never destroy the good that those of us do in the name of God,” Minister Farrakhan said.

Minietta Nelson, a former cabinet member to Mayor Hatcher, called him compassionate and a fighter, a trait needed to cut through the racism in the city and the state. As mayor, Mr. Hatcher received a lot of federal grants to the city to help with drug and alcohol addiction or to build senior housing. But once those dollars dried up, Ms. Nelson said the mayor took his cause to the state legislature.

“He knew the rights we had as a city and that is what he fought for. He had a lot of fight in him,” she said.

Mayor Hatcher chaired both Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr.’s 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns and worked as a lawyer and university professor.

Mayor Karen Freeman Wilson, who was inspired as a young person by her predecessor’s words about leadership, expressed thanks for the “life and legacy” of Mayor Hatcher. “Our city mourns a giant,” she said via Twitter.

Rev. Jackson also saluted Mayor Hatcher for his service. He called the mayor’s work with the National Black Political Convention a turning point for implementation of voting rights laws. Mayor Hatcher’s work was an extension of civil rights work in the South and the Black political convention brought Blacks from across the political spectrum together, he said. “Hatcher changed the course of our political river,” said Rev. Jackson in a statement posted on Twitter.

Despite the city’s struggles, Mr. Hatcher told the Associated Press in 2011 that he was proud of his accomplishments in office. “Maybe for some people in Gary it may not be better. But for others it may seem very much better,” he said. He married his wife, Ruthellyn, in 1976. They had three daughters, Ragen, Rachelle and Renee.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!