Chicago's new mayor faces grim reality in addressing city's violence

By Bryan 18X Crawford -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Jun 4, 2019 - 1:30:21 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot

|

After presented with information regarding the violence that took place over the long Memorial Day holiday weekend, Lori Lightfoot was admittedly taken aback.

As many as 43 people were shot, seven fatally, between Friday, May 24 and Monday, May 27. Many of the shootings were concentrated on the South and West Sides of Chicago.

Mayor Lightfoot has already pledged to make curbing violence one of her top priorities in the city, but being in her new position where she has now access to more detailed information with respect to shootings and homicides in the city sooner than most, it seems to have made her even more determined to do something about it.

“To see it graphically depicted is quite shocking and says that we’ve got a long way to go as a city,” the mayor said during a Grant Park Memorial Day celebration to honor U.S. soldiers killed during wartime. Mayor Lightfoot talked about how she gets much more frequent emails about violent crimes in Chicago now that she is mayor, and on at least one occasion, she rode with Chicago Police officers who were responding to a shooting.

“This is just an unacceptable state of affairs,” she said, adding, “This is not a law enforcement-only challenge. It’s a challenge for all of us in city government. It’s a challenge for us in communities to dig down deeper and ask ourselves what we can do to step up to stem the violence.”

The new mayor joins a long line of her predecessors who have had to deal with the ever-pervasive threat of daily violence that has existed in the city for decades. While Mayor Lightfoot has discussed plans to make gun trafficking a primary area of focus, as well as cracking down on felons who are illegally in possession of a firearm, she also said that in the areas that usually see the highest amount of crimes—primarily Chicago’s Black communities— the city must “flood these areas with a lot more resources.” But what exactly does that mean?

Mayor Lightfoot has stated, rather plainly in fact, that she feels one of the key drivers of violence in Chicago is directly related to what she calls systemic disinvestment on the West and South sides of the city—the two areas where almost all of the crime is concentrated—which leads to, as she calls it, “crimes of poverty.” However, like her mayoral predecessors, Ms. Lightfoot—at least over the Memorial Day holiday weekend—took a similar approach to curbing the violence: throwing more police at the problem. Still, with as many as 1,200 extra cops on patrol over those three days, the violence continued, and will continue as the weather outside improves. Leaving Mayor Lightfoot in a similar quandary faced by all the mayors in Chicago.

“I didn’t come into this with any illusions that we were gonna be able to wave a magic wand and reverse trends that have been in the making for some time. We were down on homicides from a year ago. But, we were up on shootings— and that’s clearly unacceptable,” the mayor said.

Unlike other Chicago mayors, Lori Lightfoot has painted herself into a corner unfamiliar amongst Chicago’s political observers. As the city’s first Black woman mayor, someone who grew up modestly in Ohio with a father who worked in a factory, a mother who worked in health care and a brother who committed one of those poverty crimes she spoke of—he robbed a bank and shot a security guard in the process— she seems to have a finger on the pulse of what has been ailing Chicago’s Black communities for decades.

Superintendent of the Chicago Police Eddie Johnson

|

“There’s young guys out there who get a small amount of money to essentially patrol their streets, but are telling me, ‘We have nothing.’ It’s difficult to make a persuasive argument not to be involved in the illegal drug trade, for example, when there are no other economic activities and opportunities out there for young men and women to participate in,” she said, adding, “The violence that plagues these economically- isolated and racially-segregated communities is also no surprise. It’s what happens when the government and private capital pull out and focus elsewhere.”

But even if corporations move out and jobs become scarce, which then forces people to turn to the streets as a means of survival, what solutions does Ms. Lightfoot have to reverse the reality and condition of Black Chicago? Ms. Lightfoot has spoken of a commitment to reinvest in the city’s roughest neighborhoods, and creating an office within her administration that focuses on providing support for victims of crimes and those who witness crimes, and providing support resources for people who come home from jail and prison, in hopes of getting them on the path of being productive citizens.

“Lori Lightfoot has identified the fact that the problem of violence in Chicago is much deeper than what people may know or understand,” Dr. Conrad Worrill told The Final Call. “We have to create a strategy to reclaim the spirit and mindset of our people. The value of life has deteriorated among certain segments of the Black community. I think Lori Lightfoot understands, from what I’ve been able to observe, the answer isn’t having a lot of extra police on the streets or doing peace marches. She seems, from what I’m getting from her, to be in favor of programmatic initiatives. And that’s what it’s going to take.”

The lack of the value for life in Chicago could be exemplified no better than in the unfortunate shooting death of 24-year-old Brittany Hill who was gunned down while shielding her one-year-old daughter from the gunfire. While two men were arrested in connection with the killing, the circumstances alone, which could’ve been much worse, left many in the city rattled and fed up with the violence.

“We are in a state of emergency in Chicago,” said community activist and former mayoral candidate Ja’Mal Green, who knew Ms. Hill personally. “I’ve lost many friends to this senseless violence and it angers me each time. Brittany left behind kids that loved and needed her. … I’m tired of saying it, I’m tired of fighting, but I can’t stop because this shouldn’t be our reality.”

After the holiday weekend, Mayor Lightfoot met personally with Chicago Police Department Superintendent Eddie Johnson, who never recovered politically or professionally in the wake of the LaQuan McDonald shooting and cover-up that ultimately led to the resignation of Lightfoot’s predecessor, Rahm Emanuel. While the pair conducted a joint press conference on Chicago’s North Side and greeted community residents who walked along Chicago’s North Shore beach, behind the scenes, Mayor Lightfoot has been working diligently in creating an air of more police accountability. Her career as a federal prosecutor, working as the head of CPD’s now defunct Office of Professional Standards, and as Police Board president, has given her a unique perspective of police and community relations, that she wants to improve in her efforts to reduce Chicago’s violence.

Brittany Hill

|

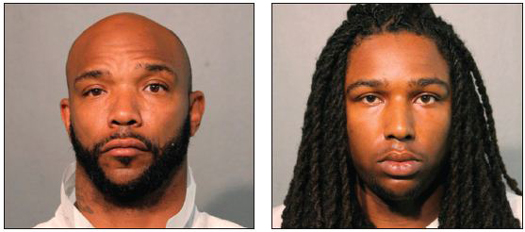

This undated photo provided by the Chicago Police Department shows Eric Adams and Michael Washington. Adams and Washington have been charged with first-degree murder in the Chicago shooting death of a woman who was shielding her one-year-old daughter from their gunfire. Authorities say Washington and Adams are due in court May 30. They are both from Urbana, Ill. The men are charged in the morning fatal shooting of 24-year-old Brittany Hill. Police believe they were targeting three people near Hill in a gang-related conflict.

|

“It’s long overdue that the City Council act swiftly in the first 100 days to pass the ordinance proposed by the Grass Roots Alliance for Police Accountability, or GAPA, to create civilian oversight of the Chicago Police Department,” she said while laying out the plan to map her first 100 days in office. “I think the plan that we have will bear fruit, but it’s not going to be instantaneous that we’re gonna see things turn around. … I don’t want to be overconfident, but I feel like we’re heading in the right direction for sure. … Don’t like leaving things to chance, so as you might imagine my team has been working diligently on this for quite some time,” she said.

“It’s going to take a deep commitment of working together between the school system, park districts, social service agencies and city officials, to reclaim the trust of the young people who have turned to the streets because they don’t have families,” Dr. Worrill explained. “Lori Lightfoot can set a tone in these partnerships by under standing what the mayor’s office can do other than flooding the streets with police. She can put a new face on the solutions to old problems in Chicago, and I think she might be moving in that direction.”

However, some aren’t convinced Mayor Lightfoot can do anything different when it comes to addressing the city’s violence than what was done before.

“Lori Lightfoot is a Trojan Horse,” Eric Russell, of Tree of Life Justice League, a police accountability organization based in Chicago, told The Final Call. “We were very disappointed in Mayor Lightfoot entrusting the public safety plan to Superintendent Eddie Johnson, who has absolutely failed us. … He has demonstrated his inability to curb the violence, not to mention his overall performance record of a 22 percent [murder] clearance rate. The problem with Lori Lightfoot is I don’t understand how she can keep using the same playbook but expecting a different result.”

Mr. Russell pointed out that Eddie Johnson has two years left in his term as Chicago’s top cop and is convinced that Lori Lightfoot, despite his less than stellar public image, and the embarrassment the CPD suffered from the LaQuan McDonald situation, is still content to let Mr. Johnson ride out his time as superintendent and collect his full police pension. This, he argues, is evidence that she isn’t as committed to improving police accountability, especially given her career as prosecutor; a job that requires a close, working relationship with police.

|

Despite her supporters, and her detractors weighing in, Lori Lightfoot has a long road ahead as Chicago’s new mayor. Can she live up to all of her promises? Probably not. No politician can. But, if she can somehow find a way to implement programs and initiatives that lead to violence prevention, while improving the relationship between the police and the Black community, and restoring the integrity of the mayor’s office, she may be able to bring about much needed change in what is one of America’s most segregated, and oftentimes, violent cities.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!